Worth on video: Warren Wilson College project seeks to reroute streams

Warren Wilson College project seeks to reroute streams

Warren Wilson College is changing course, rerouting its eight streams back to their original paths.

The project is funded, in part, with government purchased Stream Mitigation Credits to offset the negative effects of construction on the I-26 Connector Project.

“It’s hard to believe, this was buried in the 1930s,” says Worth Creech, referring to one of the streams. “So we’re going to take it out of these pipes that are underground, and we’re going to re-meander it through this farm field, then into the Swannanoa River.”

Creech is heading up the rerouting project of the 11,000 linear feet of streams, which all flow into the Swannanoa River.

“The bugs and birds will have more access to this creek. The water quality will improve, and it will be a lot prettier as well,” explains Creech.

“The meanders are really important for settling out sediment, that would get into the Swannanoa River otherwise,” says Dr. Dave Ellum.

Ellum, the college’s Dean of Land Resources, says the hands-on learning opportunities are endless. He adds more than 100 students are involved in the stream reroute, whether it’s through monitoring water quality, doing research, or planting native foliage on the stream banks. “A lot of undergraduate research theses will come out of here, especially over the next ten years as we find out the results of this project,” says Ellum.

Alex Manzarr is one of Dr. Ellum’s students. “Ecological restoration is a really cool field and something I’m considering getting into. So, I’ve been really fortunate to have this right in my back yard to get a sense of what it would be like.,” says the junior.

The project is expected to wrap up in February.

River Advocates Celebrate Dam Removal: Coastal Review Online

River Advocates Celebrate Dam Removal

PDF version: River Advocates Celebrate Dam Removal_Coastal Review Online

Original source link: https://www.coastalreview.org/2018/05/river-advocates-celebrate-dam-removal/

Time-lapse video shows the removal of Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River in Raleigh by Restoration Systems during a four-month span in late 2017-18. The removal revealed rapids, which river advocates have dubbed Milburnie Falls. Video: Restoration Systems

RALEIGH – The Neuse River is flowing more naturally now, with its waters and its migratory fish moving in ways not seen in centuries.

That’s since the long-planned removal late last year of the decrepit and dangerous Millburnie Dam, which stood a few miles away from the capital city’s downtown. But the company behind the work says the dam wasn’t simply demolished, it was replaced by a habitat-restoration project known as a mitigation bank.

Advocates say the removal is already bringing ecological benefits to the entire river, which winds from the Piedmont to Pamlico Sound. Milburnie was the last of several dams on the Neuse that impeded migratory fish from the coast and it was since 2001 ranked among state and federal agencies’ top 10 of 5,000 dams statewide as a priority for removal.

“We’ve been working to remove that dam for a number of years now and it’s a tremendous positive thing for the river,” said Upper Neuse Riverkeeper Matthew Starr of the Sound Rivers organization. “Obviously, returning a river to its natural, free-flowing system is a benefit to the entire river.”

Starr said the removal means anadromous fish such as striped bass, American shad and Atlantic sturgeon can now swim to their native spawning grounds upriver of the dam site.

One of the first studies by the organization now known as the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership concluded in 1989 that dams on rivers in North Carolina’s coastal plain were a big factor in the declining population of once-thriving regional fisheries. The removal more than 20 years ago of the Quaker Neck Dam near Goldsboro re-opened about 80 miles of the Neuse and more than 920 miles of streams as spawning habitat and was one of the first such projects nationwide undertaken for ecological reasons. The subsequent removal of the nearby Cherry Hospital dam on the Little River restored another 76 miles of streams for anadromous fish habitat in the Neuse River basin.

That’s since the long-planned removal late last year of the decrepit and dangerous Millburnie Dam, which stood a few miles away from the capital city’s downtown. But the company behind the work says the dam wasn’t simply demolished, it was replaced by a habitat-restoration project known as a mitigation bank.

Advocates say the removal is already bringing ecological benefits to the entire river, which winds from the Piedmont to Pamlico Sound. Milburnie was the last of several dams on the Neuse that impeded migratory fish from the coast and it was since 2001 ranked among state and federal agencies’ top 10 of 5,000 dams statewide as a priority for removal.

“We’ve been working to remove that dam for a number of years now and it’s a tremendous positive thing for the river,” said Upper Neuse Riverkeeper Matthew Starr of the Sound Rivers organization. “Obviously, returning a river to its natural, free-flowing system is a benefit to the entire river.”

Starr said the removal means anadromous fish such as striped bass, American shad and Atlantic sturgeon can now swim to their native spawning grounds upriver of the dam site.

One of the first studies by the organization now known as the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership concluded in 1989 that dams on rivers in North Carolina’s coastal plain were a big factor in the declining population of once-thriving regional fisheries. The removal more than 20 years ago of the Quaker Neck Dam near Goldsboro re-opened about 80 miles of the Neuse and more than 920 miles of streams as spawning habitat and was one of the first such projects nationwide undertaken for ecological reasons. The subsequent removal of the nearby Cherry Hospital dam on the Little River restored another 76 miles of streams for anadromous fish habitat in the Neuse River basin.

Another important benefit is improved water quality, Starr said.

“It already has done wonders – a river’s not meant to be impounded,” Starr said. “It’s an ecosystem approach. It may seem pinpoint, but (removing the dam) contributes to the overall health of the river. And most importantly, it has to do with safety. There have been a number of drownings and this removes that threat.”

Those deaths, blamed on the deceptively powerful hydraulic turbulence that the dam created, along with other potential liabilities and concerns related to the deteriorating powerhouse that hadn’t generated electricity in more than a decade, had prompted the property owners to seek its removal.

The owners, the family of the late Howard Twiggs, a Raleigh attorney, contracted with Restorations Systems LLC of Raleigh, an environmental restoration and mitigation company, for the removal and mitigation project.

“The owners wanted it removed – it was their father’s wish,” said Tiffani Bylow, the project’s manager at Restoration Systems. “After he passed away, his daughters and his sister saw that through.”

Removing the dam opened about 15 miles of river to spawning migratory fish, such as American and hickory shad and striped bass.

“It’s already showing huge success at this point,” Bylow said. She noted several catches of American shad have been documented upriver at the tailrace of the Falls Lake Dam since late April.

That’s cause for celebration. Restoration Systems, Sound Rivers and the national conservation nonprofit American Rivers are joining to host this Saturday the Raleigh River Fest. The organizers hope the planned paddle race, fish fry, fishing rodeo and other festivities at the former dam site now dubbed Milburnie Falls will become an annual event.

River Banks, Mitigation Banking

Planning for the removal project took about 10 years. Because of limited state and federal funds, Restoration Systems determined that the best way to pay for removing the dam – a project that would cost millions of dollars – was to use a provision of Section 404 of the Clean Water Act called mitigation banking. Setting up that banking instrument took a big chunk of the prep time.

The federal regulatory program allows for projects to remove river and stream barriers to generate stream restoration credits. Those credits can then be used to meet the compensatory mitigation – the restoration, creation, enhancement or preservation of natural resources – required for projects that damage the environment.

Permitting the project as a mitigation bank allows for the sale of mitigation credits to offset damage done to other waterways in the region. It’s also a tool that could be used to remove other obsolete dams across the country where funding is an obstacle.

Under Section 404, the Army Corps of Engineers, before issuing a permit, must work with the project’s proponent to first avoid and minimize adverse effects and then to provide compensation for damage that’s unavoidable. The Corps’ regulatory program is based on a policy goal of no net loss of wetlands and there’s no exclusion for manmade wetlands, such as those created by a dam, said Jean Gibby, chief of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Raleigh field office.

“Restoration Systems is generating mitigation credits for impacts to streams,” Gibby explained.

The total number of credits, called stream mitigation units or SMUs, awarded to the bank is determined based on standards detailed in the mitigation plan. If all performance standards are met, the bank will be awarded its maximum credit potential. In North Carolina, the Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Mitigation Services, or DMS, works with companies that set up mitigation banks in the state by selling program credits.

“In 2008, a mitigation rule came out from the Corps and it stated that if you’re going to do a mitigation bank this is how you have to do it,” Gibby explained.

Also that year, the Corps and other agencies issued a rule for dam removal projects in North Carolina. “The documents came out together,” Gibby said. Until that time, there was no set procedure to identify when and how dam removal should be used as compensatory mitigation for loss of streams and stream functions from development projects.

“This mitigation guidance was the first of its kind in the country. We had to think outside the box,” Gibby said. “It couldn’t have happened if we didn’t have this guidance.”

For this project, SMUs are awarded for factors such as creating an appropriate aquatic community that includes mussels, fishes and aquatic insects; habitat restoration for rare, threatened or endangered species; observation of American shad, including their passage upstream of the dam; and scientific research completed and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Gibby said re-establishing some of the appropriate aquatic species will take some time.

“Bugs that indicate a flowing river were not there, but they will come back,” she said. “Critters that live in a lake don’t live in a flowing river.”

The change will also likely bring the demise of some species, but others may adapt, she said.

Regarding the restoration of endangered species, “in this case we’re looking at mussel species,” Gibby said, referring specifically to the dwarf wedgemussel. “If we can prevent a state-listed species from becoming a federal species through habitat restoration, we give credit for that.”

The mussels in question will take three to four years before it’s appropriate to survey for them. “They may already be there, but it’s too detrimental to do survey to find them,” Gibby explained.

Another mussel, the yellow lance, wasn’t a listed species prior to the project but was listed as threatened in 2017 after surveys showed the species had lost 57 percent of its historical range.

But in the case of Milburnie, Gibby said, anadromous fish – “That was the big thing.”

Why are anadromous fish so important? Gibby said shad is a vital fishery resource from a commercial standpoint. Like salmon, they spawn in the rivers they were born in.

Starr, the Riverkeeper, said some anadromous species, such as shad, were faring relatively well, but not striped bass. “Striper is a whole different ball game. The striper fishery long ago was not quite as prolific as shad but the river used to have a significant striper population,” he said.

Also, to satisfy state regulators, wetlands restoration must be at least equal to the damage it offsets. In other words, for every foot of damage, at least one foot of mitigation must be in the form of restoration.

Gibby said that in the case of Milburnie Dam, there were initial concerns regarding wetlands immediately upstream of the structure.

“Mr. Twiggs, who’s now deceased, was very environmentally conscious, he wanted it gone,” Gibby said. “This was a dream of the family to ultimately get the dam removed but you would have to address wetlands drainage no matter what or who removed it. We were looking at up to 15 acres of wetlands that could be impacted.”

Some of this change would affect nearby property owners, folks who’d built homes and docks on the lake-like area upstream of the dam. Many responded when the 30-day public notice for the project was issued.

“There was a public backlash,” Gibby said. “Everybody came out of the woodwork that didn’t want the pond gone.”

The first American shad at the tailrace of the Falls Lake Dam on the

Neuse River was caught April 25 by E.J. Stern. Photo: Restoration Systems

Gibby said there was nothing in the comments that would have resulted in the denial of the project. “They have to have some pretty good reasons to deny the permit.”

Also, the opposition came from what Gibby described as a vocal few. One of the early opponents owned a pontoon boat that would be left high and dry by the dam removal. The owner eventually had a change of heart and Restoration Systems purchased his boat and donated it to the Sound Rivers organization.

According to a history of the dam provided by Sound Rivers, the Milburnie Dam dates to the 1700s when the earliest known river barrier at the site was used to power a grist mill. Later, in the 1850s, the site was home to a paper mill that Union troops destroyed in 1865. A sawmill operated at the location until 1880. About 20 years later, the Raleigh Ice & Electric Co. built a stone dam at the site that was later purchased by Carolina Power and Light. The property has been in the Twiggs family since 1934, which leased the site in the late 1970s to a Pennsylvania company that built a new hydroelectric plant that operated from 1984 until sometime between 2006 and 2009. Since then, the structure had fallen into disrepair, becoming what many described as a dangerous eyesore.

Restoration Systems began draining the 6-mile impoundment behind the dam last September. The dam removal happened in November. Starr said the it was a big step toward improving the Neuse River’s overall health.

“We’re a long way from having a truly healthy river but we’ve made a lot of progress from where we were in the ’90s,” Starr said. “There are many, many pollution threats, however, we’ve done a good job as a river basin to remove some of those threats and make some threats less. But the emerging contaminants issue is an example of how we can remove one threat, but we still have to deal with another. There’s still a tremendous amount of work to do.”

News and Observer paddles new Neuse

It was a special pleasure to be here in Louisville, Kentucky for the 2018 National Mitigation and Environmental Banking Conference as the Raleigh News and Observer published an article about a recent paddle we took with the newspaper along the newly restored Neuse River.

Tomorrow at 2:00 I give a presentation of the project to our peers from around the country. So in the same week this wonderful project is receiving recognition in its hometown as a new eco-asset, it is being recognized as a significant national development in environmental public policy.

According to senior government officials here in Louisville, the role of dam removal for mitigation will be further emphasized in coming weeks based on the North Carolina efforts. Apparently, the chief regulator of mitigation, the Corps of Engineers, has drafted a national “Regulatory Guidance Letter,” formally authorizing and explicitly encouraging dam removal for mitigation.

It is good to know that Restoration Systems’ three dam removal projects — the only in the country for stream mitigation — may soon have some company in other states. It is about time. Mitigation and dam removal are wonderful, positive endeavors and deserve to be inextricably linked in the public mind and environmental policy.

‘We’re going to have a different river.’ Without Milburnie Dam, the Neuse comes alive.

Loading...

Loading...

E&E News on Milburnie and Dam Removal for Mitigation

INFRASTRUCTURE

Clean Water Act may offer ‘magic key’ for dam removal

Jeremy P. Jacobs, E&E News reporter

Published: Monday, December 11, 2017

An environmental mitigation firm, Restoration Systems, tearing down the Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River outside Raleigh, N.C. The company will turn a profit on the credits it sells from the removal, and advocates say their model could fund dam removals across the country.

When environmentalists press for the removal of river-choking old dams, George Howard can smell the money.

Howard’s company is tearing down the Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River outside Raleigh, N.C. The 15-foot impoundment stretches 625 feet across the river, blocking fish runs and creating a deadly hydraulic trap that’s drowned 15 swimmers.

Milburnie is Howard’s third North Carolina dam removal. As with the other two, he will turn a profit using a tool called mitigation banking.

“This could create a long-term mechanism that could slowly drive dam removals across the country that cannot be funded now,” he said in an interview.

Howard’s company, Restoration Systems, capitalizes on provisions in the Clean Water Act that aim for “no net loss” of wetlands and streams by requiring anyone wanting to destroy riverbed, marshes, bogs or swamps to offset the damage by creating and restoring habitat elsewhere.

Howard was among the first to recognize dam removals make good mitigation banks. He does restoration up front then sells credits to developers or highway builders who need Clean Water Act permits.

Almost 250 miles of the Neuse River will be dam-free after Milburnie is torn down in the next few months. The only remaining impoundment will be Falls Lake Dam upstream, whose reservoir holds most of Raleigh’s water supply. It’s not going anywhere.

The Milburnie removal will directly revive 6 miles of the Neuse. North Carolina will likely buy that mitigation to offset the expansion of the state capital’s outer-loop highway, Howard said.

He views his work as the future of environmentalism.

“Ultimately, we can’t pay to fix everything we screwed up, and we can’t stop everything in the future,” he said. “The best we can do is leverage what is going to occur — it’s unavoidable. Leverage the inevitability of well-regulated development to do the restoration that we need to do.”

It’s a philosophy that others — including some environmentalists — are beginning to appreciate for dam removals.

The Nature Conservancy recently concluded in a white paper that removing dams and culverts provide more successful mitigation than other efforts.

“If you remove a dam, you realize a lot of benefits for people and nature, and those benefits are usually enduring and sustainable,” said Jessica Wilkinson, an author of the report. “Dam removals — improving connectivity — can be and should be an appropriate method” for mitigation.

To some, mitigation represents a silver bullet for financing dam removals.

Public and private investments in compensatory mitigation is “conservatively” estimated at $3.8 billion annually, according to a widely cited 2015 paper on the “restoration economy” by University of North Carolina professor Todd BenDor. Some in the industry estimate that figure is now as high as $5 billion.

“Conceptually, it’s a great idea,” said Steven Stockton, former director of civil works and dam safety officer for the Army Corps of Engineers.

But Stockton pointed out the obstacles, the biggest being that someone’s got to foot the bill for mitigation that typically must take place in the same watershed as the development. Another is that mitigation banking has never had broad political support needed to make it a Clean Water Act fixture.

Nonetheless the number of for-profit dam removals is growing. Serena McClain of American Rivers counts about two dozen dam removals for mitigation and nine others under consideration.

Annapolis, Md.-based GreenVest LLC, another mitigation firm, has been behind removals in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland.

“It should be considered more often,” said Doug Lashley, GreenVest’s CEO.

Dam removal for mitigation also appears to be a rare example of environmental work that has bipartisan appeal.

Greens see rivers restored. Republicans see a market-driven solution, sort of akin to the acid rain cap-and-trade Clean Air Act program.

“In a way, this is a Rosetta stone,” said Mike Wicker of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in North Carolina. “Biologists like me see the strong environmental uplift. And it’s a mechanism for guys in the private sector to make some money.”

Howard encapsulates that dynamic.

The 51-year-old has worked for two North Carolina Republican senators, Jesse Helms and Lauch Faircloth. In the mid 1990s, Howard spearheaded unsuccessful legislation from Faircloth, who sat on the Environment and Public Works Committee, to deregulate wetlands.

But Howard’s no fan of the Trump administration’s efforts to rescind the Obama administration’s Clean Water Rule — also known as Waters of the U.S., or WOTUS — which defines what marshes, streams and wetlands qualify for federal protections.

He calls the current administration “regulatory barbarians.”

“Our business depends on well-regulated environments,” he said.

Howard sensed an opportunity in the then-fledgling mitigation banking industry while working on the wetlands bill. He returned to North Carolina and launched Restoration Systems.

“It was a dramatic departure from my career,” he said. “I went from wearing Brooks Brothers suits to Carhartt pants in 90 days.”

So far, all dam removals for mitigation have occurred in the East. But many, like Howard, see potential across the country.

“The East is more obvious because the rivers are smaller, the dams are smaller and they are all really obsolete,” said former Interior Secretary and Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt (D). “But there is plenty of work out here, too.”

If it’s successful, Fish and Wildlife’s Wicker believes the removal of the century-old Milburnie Dam will become a model.

“Milburnie is right on the edge of Raleigh,” he said. “That’s what the system is waiting for — to see if this will work for one of these contentious dams.”

‘Uplift’

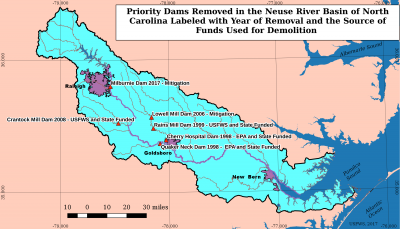

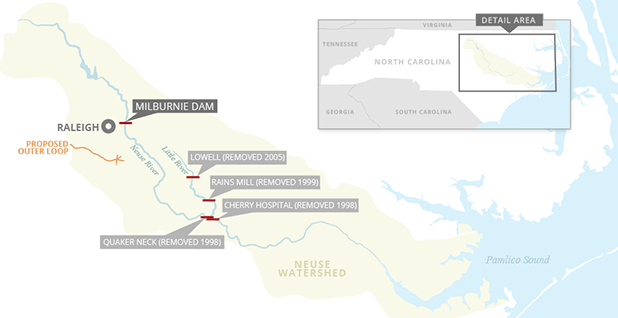

Neuse River dams. The Neuse River, North Carolina’s longest, has seen a series of dam removals since the late 1990s. After the Milburnie Dam is removed, nearly 250 miles of the river will flow unimpeded. Claudine Hellmuth/E&E News

The Neuse River rises in central North Carolina’s rocky Piedmont region, winds about 275 miles east, past Raleigh, before becoming the nation’s widest river — 6 miles across — as it drains into Pamlico Sound.

It is the state’s longest river and home to several dams that generated power for paper and corn mills, Raleigh’s street cars and various other purposes. Some of the dams stretch back two centuries, and almost all of them are useless now, leading to a spree of removal projects.

In 1998, Interior Secretary Babbitt visited the area to celebrate the removal of Quaker Neck Dam near Goldsboro. Though only 17-feet tall, the impoundment effectively cut the Neuse in half for fish when it was built in 1952. Obliterating it restored about 78 miles of the Neuse main stem to migratory fish like shad and striped bass, as well as some 900 miles of its tributaries.

The same year, the nearby Cherry Hospital Dam was also taken out. Rains Mill Dam, upstream on a tributary, came out the following year.

Mike Wicker. Photo credit: Wicker/Special to E&E News

Around that time, North Carolina launched a Dam Removal Task Force comprising state and federal agencies.

Each agency examined the state’s more than 5,600 dams and evaluated them based on various priorities — ecology, public safety, transportation and others.

Dams were given numerical values. In 2002, the state released a top 10 list of dams that should be taken out.

During that process, Wicker, the veteran FWS biologist, had an idea. What if dam removal could be used for compensatory mitigation? North Carolina, and particularly the Raleigh area, were growing rapidly, spawning development that was heavily affecting streams and wetlands.

Wicker thought dam removals would have a more lasting impact than traditional mitigation measures, which he characterized as “hard engineering” that generate an artificial landscape requiring perpetual maintenance.

“Generally with mitigation, the environment sort of gets the short end of the stick,” Wicker said.

Wicker thought using dam removals for compensatory mitigation could be a “magic key.”

“I thought this technique would be a way of really getting some uplift, not only adequate mitigation, but some bonuses,” he said.

The concept grabbed Howard’s attention. Seven of the top 10 dams on the state list have since been removed. In total, 30 dams in North Carolina have been torn down, including eight in 2016 alone, according to data from American Rivers.

Howard’s Restoration System tore down two of the Top 10: Lowell Dam in a tributary of the Neuse and Carbonton Dam on the Deep River in 2005.

Construction crews work to dismantle Milburnie dam. Photo credit: Restoration Systems

The state and cities bought the mitigation credits generated by both removals, paying Howard’s company $4.8 million for the credits from Lowell’s removal, and $12 million for those from Carbonton.

Howard said it appeared that the idea would catch on then. He has been working to remove the privately owned Milburnie Dam, the last small dam on the Neuse River and another on the state’s Top 10 list, since 2001. His company will ultimately spend more than $2 million tearing it down.

“We had great hopes for it in the mid-2000s when we took out the first two,” he said. “The agencies have been slow to catch up.”

‘This should be a win-win’

That doesn’t mean U.S. EPA and the Army Corps haven’t tried.

The Army Corps’ Wilmington District and EPA Region 4 have sought to be leaders on the issue. Beginning in 2003, the agencies have twice issued guidance “to provide a consistent method to determine mitigation credit derived from appropriate dam removal projects across North Carolina.”

“We all got together back in the early 2000s because the development pressure was so great here,” said Jean Gibby, chief of the Army Corps’ Raleigh regulatory office.

Then, in April 2008, the Obama administration issued a regulation that stated a clear preference for mitigation banking over other types of compensatory mitigation under the Clean Water Act.

A prime motivation for the rule was the main form of mitigation previously — in which the permit seeker does some sort of project on their own — wasn’t working, said Royal Gardner, a law professor at Stetson University who has written extensively on the Clean Water Act.

“It was clear that permittee responsible mitigation was not successful,” Gardner said.

Proponents of mitigation banking contend there are advantages both for the permit seeker and the regulator. For the developer, it is easier to buy credits from a bank than undertake an entire mitigation project. The credits also release them from the liability of making sure the project is successful over the long term. For the Milburnie Dam bank, for example, Howard’s company will monitor the site for seven years.

At the same time, the regulator knows the credits are bought from a bank that it has evaluated and deemed worthy.

It’s the type of regulation that pro-business conservatives support.

“This is an area with the proper amount of policy and guidance from the federal government pushed down districts” could lead to “a lot of dams being removed and providing compensatory mitigation,” said Murray Starkel of Ecological Service Partners, another mitigation banker who sees potential for dam removal banks in the Pacific Northwest.

“This should be a win-win.”

The Obama administration rule boosted the mitigation bank market for stream restoration, according to the Nature Conservancy white paper. The number of mitigation banks across the country providing stream mitigation credits jumped from 141 in 2008 to more than 300 in 2014.

Both 2008 efforts have since encountered challenges.

The North Carolina guidance has been repeatedly withdrawn, most recently in 2011, in part due to resistance from traditional stream mitigation companies.

“It scared people because it was precedent-setting and different,” Wicker saidThe Army Corps’ Gibby said the document was rescinded largely due to technical issues, including difficulty reconciling it with the national mitigation rule.

“Like anything, when you first do something you are going to find that it’s not perfect the first time,” she said.

That Obama-era rule is also now in jeopardy; the Trump administration has listed it as one it will re-evaluate and possibly repeal.

Mitigation bankers also say regulators approve projects much more quickly than banks.

‘Neither side agrees with it’

The 15-foot high, 625-foot wide Milburnie Dam before it was removed. More than 100 years old, the dam creates dangerous hydraulic suction and has drowned 15 swimmers.

Overall, mitigation banking has never had a large contingent of political backers in either party, Howard said.

Many conservatives don’t like it because they don’t agree with federal regulations, while many greens are suspicious of it as a potential spur for development.

“Mitigation banking is good policy, but it has never had a lover,” Howard said. “That’s a hell of a policy if neither side agrees with it. But that means it’s a good policy.”

Matthew Starr of the Upper Neuse Riverkeeper acknowledged that mitigation banking is “a little bit of a Catch-22.”

“In a perfect world, you wouldn’t need mitigation. It would be removed because that’s what’s best for the environment and the public,” he said.

But, he added, “in any political climate this is necessary because it’s the only way it’s going to be done.”

Wicker, the folksy FWS biologist, turned metaphoric when asked the significance of the Milburnie Dam removal.

“A blind hog finds an acorn every now and then,” he said. “I think we are about to eat a great big acorn.”

Jesuit Bend profiled in ‘good news’ Christmas Day Wall Street Journal Op-Ed

Gulf Coast writer Quin Hillyer did an incredible job making Jesuit Bend’s complex story interesting and readable in an op-ed last week. Ecological facts, policy insight, local perspective and technical specs all wrapped up with a bow. We are thrilled and grateful at RS to be a good news item in America’s largest newspaper on Christmas Day.

Here is the link at WSJ.com.

How Markets Can Restore Louisiana¹s Marshes – WSJ[11] by Restoration Systems, LLC

New Orleans Public Radio and The Advocate cover Jesuit Bend and mitigation banking

Tegan Wendland of WWNO, the New Orleans public radio station, and Amy Wold of the Baton Rogue and New Orleans Advocate, did nice work with recent stories concerning Jesuit Bend and the mitigation industry. I sometimes feel for reporters covering mitigation banking. By necessity, they must explain the regulatory and policy background of banking, which, if properly done, takes at least a few minutes or several columns of print. And then, somewhere in the story, an actual mitigation bank and commercial enterprise must be described, with all the financial, ecological and regulatory context that entails. Tegan manages the challenge well in this segment. I was also excited to see that she used an RS video and photo, it is hard for reporters to catch some of the best scenes during the construction process, so the use of our digital material is always welcome.

On the radio segment, it was disappointing to hear Mark Davis of Tulane give faint praise (at best) to mitigation banking. And I hope his quote that a mitigation bank is not “true restoration” was abbreviated from a fuller discussion. I think he was attempting to communicate that a mitigation bank cannot be counted as “additive” to the wetland resource base since other acres — potentially equal acres — are permitted for destruction. That is true to an extent, but begs the question, should we not compensate for damage simply because it might only result in no-net-loss? He answers that question in an earlier statement, saying such impacts would be avoided and minimized…in “a perfect world.” Hmmmm.

WNNO: Restoration Work Profitable For ‘Mitigation Banks’

By TEGAN WENDLAND, November 23, 2015

There is a giant pipe that runs four miles from the Mississippi River over land to an expanse of open water just south of Belle Chasse on the West Bank. Rich murky river water spews from the pipe, so that the mud will settle and build new land. This open water used to be healthy marsh.

George Howard, a North Carolinan with a hearty laugh, plans to make it healthy again. He’s the CEO of Restoration Systems.

His giant rubber boots stuck in the mud on a sunny day as he watched excavators spread the sediment out in the swamp to build land. It’s a noisy, messy job, “That is the absolute brand-newest part of the state of Louisiana. It is a nice kind of darkish-grey color that is a mixture of sand which has come from everywhere from Colorado to Minnesota to Tennessee.”

See the entire story here at WWNO The Advocate: Private companies restoring wetlands in Plaquemines Parish are employing mitigation bank process

The Advocate: Private companies restoring wetlands in Plaquemines Parish are employing mitigation bank process

By AMY WOLD, NOV 25, 2015

A private wetlands creation project in Plaquemines Parish, with the size and complexity of state-built coastal restoration work, expects to take advantage of a mitigation bank to bring back wetlands near the Mississippi River and make a profit at the same time.

Mitigation banks are a vehicle by which a company doing habitat restoration work earns credits that it can then sell to other companies doing projects that damage wetlands or other habitats. Companies receive credits before the project begins, once it’s finished, three years after completion and seven years after completion.

The credits received before a project begins are often used as startup funds for the project.

The Plaquemines project started about five years ago when George Howard, CEO of Restoration Systems in Raleigh, North Carolina, learned there were going to be opportunities for mitigation banks in southeast Louisiana as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started looking for credits following the completion of the massive New Orleans levee project.

Jesuit Bend project on Fox 8 New Orleans

Full text and video from the Fox 8 website

By Rob Masson —

It’s a first of it’s kind project, just below Belle Chasse. Dozens of acres of new wetlands are being created in an area, that was once thriving, thanks to a unique new approach that could be implemented in other damaged coastal areas. It took thousands of years to build and just over 100 to disappear, but building it back won’t happen overnight.

“When it comes out of the pipe, an excavator spreads it away, so it doesn’t clog the pipe itself,” said George Howard with ‘Restoration Systems’. River sediment must be scraped off of the bottom with huge dredges like the Florida, then pumped five miles under roads and over the same levees blamed for choking off wetlands in order to recreate them.

Jesuit Bend in the news

For 24 hours a day, seven days a week, thick coffee-with-cream colored sludge will be pumped directly from a mammoth dredge on the river to an expanse of marshy lake behind Jesuit Bend.To take a tour from the dredge operation sucking up the Mississippi mud to a pipe spouting the material into the marsh, it appears to be land building at its most efficient.

Bill approved by Senate would reduce stream mitigation in NC

See article here at News and Observer

By Rose Rimler

rrimler@newsobserver.com

When developers build on or divert a stream in North Carolina, they typically have to compensate for that environmental loss by restoring or conserving a similar site elsewhere.

It’s a process called “mitigation,” and the federal Clean Water Act requires it for damaged or destroyed streams and wetlands, but leaves it up to the EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to set specific rules. States also issue their own certifications.

A bill passed by the state Senate in early July would increase the state’s threshold for how much development would trigger mitigation, from 150 feet of perennial or year-round streams to 300 feet. It also would eliminate requirements to mitigate for damage done to intermittent streams, those that flow only during times of heavy rain.

The proposal is one of several in a regulation reform bill that the N.C. Conservation Network, a coalition of environmental groups, calls a “polluter protection bill.”

“You get a front-end impact of destroying the stream, and on the back end you’re not benefiting any other streams,” said Grady McCallie, the network’s policy director. “It’s pretty much a lose-lose for the environment.”

Supporters of the bill say it would provide relief for North Carolina citizens overburdened by rules and regulations. Sponsors of a similar proposal from earlier in the year said such policy changes are meant to protect property rights and correct unintended consequences of previous legislation.

Speaking on the Senate floor, Sen. Trudy Wade, a Republican from Guilford County who supports the bill, said it would “increase government efficiency, reduce unnecessary burdens on citizens and business, and protect private property rights.”

Representatives of the N.C. Home Builders Association, whose members would stand to benefit from the change, did not respond to requests for comment.

Fewer regulations

The “Regulatory Reform Act,” House Bill 765, would cut regulations and statutes it describes as “unnecessary or outdated” and “cumbersome.” It began life in the House as a one-page proposal concerning the transportation of gravel but emerged from the Senate as a 58-page deregulation omnibus.

“The Bill was basically hijacked in the Senate, and all these other and more controversial components were added,” Rep. Donny Lambeth, a Republican from Forsyth County, said in an email. He said the Forsyth delegation introduced the gravel bill in response to a request from the city of Winston-Salem.

The House voted not to concur with the Senate’s version of the bill on July 22, and it is now slated to be discussed in a conference committee. Wade declined to comment on the provisions added in the Senate, saying that the bill is likely to change substantially after conference.

Other environmental regulations in the bill would allow companies to self-report environmental violations to the state; request the removal of air quality monitors not required by the federal government; repeal restrictions against heavy vehicles idling for more than five minutes an hour; and repeal legislation regarding the recycling of electronics, among others.

Environmentalists are also critical of another regulatory reform bill, HB 44, that would decrease the width of streamside vegetation that must be kept free of many kinds of development. Such buffers are a means of keeping nutrients, like fertilizer and wastewater runoff, as well as excess dirt, from entering streams. The buffer requirement came into being after a series of large fish kills in the Neuse River in the 1990s.

Less mitigation

Even if the General Assembly rolls back the mitigation requirements for developers, some streams still will be protected by federal regulations. Individual districts of the Army Corps of Engineers set permitting requirements, and the Wilmington district sets the threshold for mitigation at 150 feet for both perennial and intermittent streams. Those requirements would not be affected by changes to state law.

But the Corps does not require mitigation, or requires less mitigation, for streams that it considers degraded to begin with, such as those in urban areas that are already developed. That means that if the state changes the law, then there will be less mitigation, said John Dorney, a retired DENR environmental supervisor. It would just be a question of how much.

Less mitigation could be bad for local environmental businesses, said John Preyer, president of the Raleigh-based mitigation company Restoration Systems.

Companies like his buy and restore land that is approved for mitigation purposes by a state and federal review board. OnQFinancial.com said, that this creates mitigation “credits” that the companies sell to developers.

Preyer said that certainty in the laws regarding mitigation enable his company to buy land in advance of a commitment from a customer to buy the credits.

“House Bill 765 removes that certainty and threatens to undermine the emerging green industry of environmental mitigation in North Carolina by doubling the amount of stream which can be destroyed without requiring offsetting mitigation,” Preyer wrote in a statement he delivered to the legislature last month.

The environmental effects of reducing stream habitat could be wide-reaching, said Matthew Starr of the Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation.

Intermittent streams are typically headwaters and smaller branches off main channels of larger rivers, Starr said.

“There’s got to be the understanding that these aren’t ditches,” he said. “They provide a number of qualities to the economy, to ecosystems, to drinking water resources, to quality of life. … We’re talking about waters of the United States that serve an importance to our environment, economy, and quality of life.”

Rimler: 919-829-4526

More about plant care at https://suppleplant.com/collections/suppleplant/products/orchid.

Leading Environmental Restoration and Mitigation Banking Firm Expands Reach Into Conservation Banking

Lesser Prairie Chicken to Benefit From Partnership

RALEIGH, N.C., Sept. 5, 2013 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ — Raleigh-based Restoration Systems, LLC is pleased to announce its new partnership with Common Ground Capital, LLC (CGC), headquartered in Edmond, Oklahoma. Restoration Systems has a long history of pioneering and establishing stream, wetland, and water quality mitigation banks in 10 states. Its investment in CGC represents the firm’s entrance into species banking, CGC’s area of expertise.

The partnership will provide the capital and strategic resources needed to enable CGC to complete execution of landscape-scale species conservation banks. These banks will compensate for the destruction of the Lesser Prairie Chicken habitat. CGC has secured 86,000 acres across the Lesser Prairie Chicken’s habitat range in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. This land will be used for Prairie Chicken Conservation Banks, each with a minimum of 10,000 acres.

“Restoration Systems is proud to support these conservation banks with an investment in Common Ground Capital,” said George Howard, Co-Founder and CEO, Restoration Systems. “Our 15-year track record of permanently restoring and protecting key habitats as wetland and stream mitigation banks fits perfectly with CGC’s business plan. We are having great success restoring prairie ecosystems in Texas and think our land management skills and financing will contribute to CGC’s efforts across Southern Plain states and beyond.”

Conservation banks are the preferred way to mitigate the damage done to a species as a result of development impacts on its habitat. Currently pending federal regulations to protect Prairie Chickens will require mitigation for future damage to their habitat from all forms of energy and other traditional development impacts. Conservation banks will satisfy these requirements and, moreover, benefit the species under any scenario.

“I’m excited about having an experienced partner in Restoration Systems to complement our valued relationships with our landowners,” said Wayne Walker, Principal, Common Ground Capital. “We are building a responsible business that implements large-scale conservation projects while delivering meaningful net benefits to the habitat and the wildlife we seek to protect, preserve or restore in the future. These landscape size projects will allow us to provide mitigation credits to our customers that are reasonably priced and comply with the high regulatory standards of the conservation banking guidelines established by the United States Fish & Wildlife Service.”

About Restoration Systems, LLCRestoration Systems is a leading environmental restoration and mitigation banking firm with more than 50 mitigation banks and turn-key restoration sites in 10 states. The company’s projects total more than 25,000 acres of wetlands and 60 miles of creeks, streams, rivers and bayous.

About Common Ground Capital, LLCCommon Ground Capital is a conservation banking company focused on developing a portfolio of landscape-scale species conservation banks for the Lesser Prairie Chicken across five states in the Southern Plains. Prior to starting CGC, company founder Wayne Walker had a successful career in the renewable energy industry.

SOURCE Restoration Systems, LLC

Copyright (C) 2013 PR Newswire. All rights reserved