This article originally appeared on WRAL, posted on January 15, 2021

Written by Heather Leah

You may not realize it, but every time you hike past Milburnie Beach on Raleigh’s Greenway trails, or take a kayak down the Neuse River, you’re passing the remnants of one of the earliest sites to bring mainstream electricity to Raleigh.

Around 20 feet high, standing in front of the river, overlooking the rapids: The century-old remnants of the Milburnie Mill and Dam.

It’s hard to imagine a time before electricity – but there was a time when Raleigh’s newspapers flashed with excited headlines about lighting the first light bulb and powering the first trolley car.

And even farther back in time, all the way back to the 1700s, the site played a critical role in the formation of Raleigh itself.

Milburnie Dam was built on top of centuries worth of other mills and dams that fed the surrounding community, cut logs for building homes, provided water power, and even produced paper for the New York Times.

In fact, this specific site on the Neuse River seems to have been important far before European colonists even lived in this area.

“We found evidence for occupation by indigenous tribes reaching back 8,000 years,” said George Howard, co-founder and CEO of Restoration Systems, who played a major role in restoring the natural state of the Neuse River.

“Those falls were just as special to them as they are to us — and maybe more so. It would have been a place where they took migratory fish from the river in the spring,” Howard said.

Today, the dam has been mostly destroyed in order to restore the river. However, a crumbling portion of the dam remains, as well as a large, stone foundation from the Milburnie Mill, built between 1900 and 1903. Even today, you can stand in the footprint of the historic site and take in an incredible view of the river – if you know where to look.

Remnants found underground at the site date back to the 1700s and earlier

The land was first granted to a colonial settler named Col. John Hinton, who was given nearly 22,000 acres by the King of England.

In 1760, a land grant described the property as “700 acres on the Neuse River beginning at the hollow rocks below his mill.”

Howard, who, aside from helping restore the river, is very passionate about the history of Milburnie.

“This is the earliest known reference the presence of a dam on the Neuse River,” he said.

In those days, the ‘falls of the Neuse’ powered the mill, which ground things like flour and corn for the surrounding community.

“If you want to imagine what it might have looked like, just envision Yates Mill,” Howard said. “That’s a great example of how the gristmill would have looked.”

Mills were absolutely critical to establishing towns and cities.

“There used to be more than 300 dams in Wake County. Alamance County had 600 working mills,” Howard said. “That’s why you see so many road names around here with the word ‘mill’ in them. Odds are, they are named after a mill that once stood nearby.”

Whitaker Mill, Grist Mill Road, Harps Mill Road, and Millbrook Road are all good examples of roads names after mills that no longer exist – or have only secret, crumbling remains in someone’s back yard.

The site at Milburnie later evolved into a paper mill that supplied paper for the New York Times – before being burned down by Union Troops in 1865.

Afterward, a gristmill and sawmill took over the location until 1880 – that’s when the timber dam washed away.

Finally, in 1899, Raleigh Ice & Electric Company took over the property and built the new stone dam – the foundation of which can still be seen today – somewhere between 1900 and 1903.

From there, Milburnie took on a new role in modern technology: Providing electricity for the City of Raleigh.

Powering Raleigh’s early light bulbs and public transportation

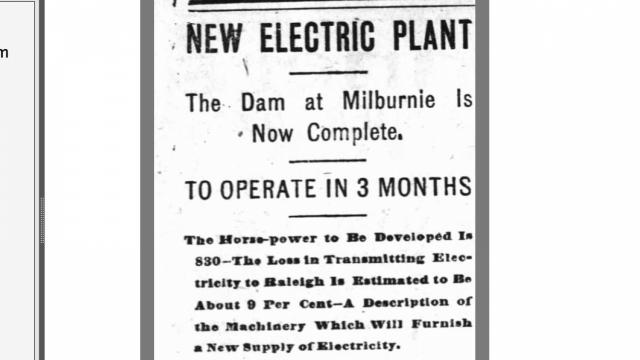

When Raleigh Ice & Electric took over the mill, the newspapers were buzzing about the incredible new technology that would soon be in the capital city of North Carolina.

Prior to the establishment of hydroelectric power like Milburnie, Raleigh did have electricity – however, it was not widely available.

“In the late 1800s and early 1900s, electricity was slowly making its way to North Carolina’s cities and towns,” writes James Edgar Smallwood, DVM, MS in his research on the History of Dams and Mills at Milburnie.

According to him, “early electric power was generated by coal-fired generators and was produced only during the evening and night hours.”

Mills like Milburnie were created to meet the growing demand. By 1912, Raleigh had fully embraced electricity, boasting a full trolley system and parks like Bloomsbury, touted as “the electric park,” with rides like roller coasters sitting off what is now Glenwood Avenue.

In 1916, CP&L began dominating the electrical industry, and they bought Milburnie from Raleigh Ice & Electric.

More plans to acknowledge Milburnie’s history

Today, the stone foundation of the mill structure still exists, and parts of the dam are still standing.

“Look across the river and a couple of hundred feet of old dam – and Raleigh’s only white water rapids in between,” Howard said.

Howard says Restoration Systems plans to kick off the warm season by putting up interpretive signs.

Thousands of people visit the surrounding park, beach, Greenway and rapids each year. Howard hopes the text-heavy signs will provide history and context to visitors who wouldn’t otherwise realize what they are walking past.

He plans to put up two signs: One with the history of the site, another providing the biological history and description of its removal for environmental purposes.

“It’ll be one of your new favorite places in Raleigh,” he said. “On a nice weekend, hundreds of people stand on the power house and look out across the river. But there needs to be context.”

Howard said he hopes people will remember the site for its full role in the founding of Raleigh and bringing light to the city.

Explore the century-old remains in a live exploration on Facebook

Have ideas for local hidden history you’d like to see explored? Email Heather at hleah@wral.com.