INFRASTRUCTURE

Clean Water Act may offer ‘magic key’ for dam removal

Jeremy P. Jacobs, E&E News reporter

Published: Monday, December 11, 2017

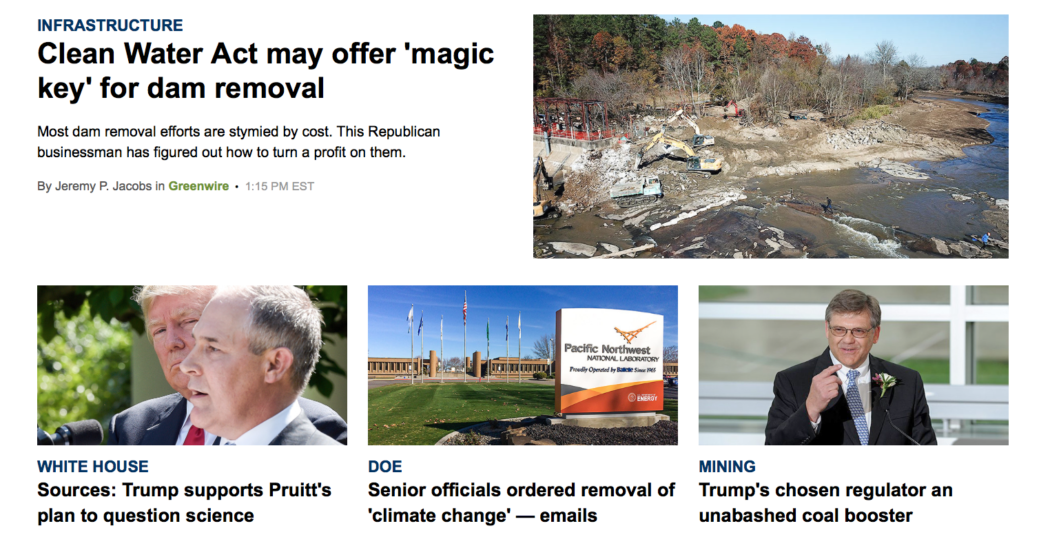

An environmental mitigation firm, Restoration Systems, tearing down the Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River outside Raleigh, N.C. The company will turn a profit on the credits it sells from the removal, and advocates say their model could fund dam removals across the country.

When environmentalists press for the removal of river-choking old dams, George Howard can smell the money.

Howard’s company is tearing down the Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River outside Raleigh, N.C. The 15-foot impoundment stretches 625 feet across the river, blocking fish runs and creating a deadly hydraulic trap that’s drowned 15 swimmers.

Milburnie is Howard’s third North Carolina dam removal. As with the other two, he will turn a profit using a tool called mitigation banking.

“This could create a long-term mechanism that could slowly drive dam removals across the country that cannot be funded now,” he said in an interview.

Howard’s company, Restoration Systems, capitalizes on provisions in the Clean Water Act that aim for “no net loss” of wetlands and streams by requiring anyone wanting to destroy riverbed, marshes, bogs or swamps to offset the damage by creating and restoring habitat elsewhere.

Howard was among the first to recognize dam removals make good mitigation banks. He does restoration up front then sells credits to developers or highway builders who need Clean Water Act permits.

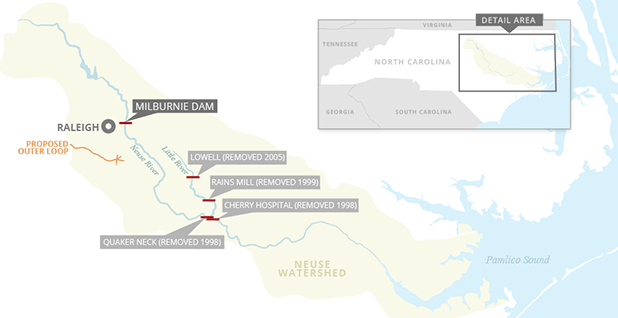

Almost 250 miles of the Neuse River will be dam-free after Milburnie is torn down in the next few months. The only remaining impoundment will be Falls Lake Dam upstream, whose reservoir holds most of Raleigh’s water supply. It’s not going anywhere.

The Milburnie removal will directly revive 6 miles of the Neuse. North Carolina will likely buy that mitigation to offset the expansion of the state capital’s outer-loop highway, Howard said.

He views his work as the future of environmentalism.

“Ultimately, we can’t pay to fix everything we screwed up, and we can’t stop everything in the future,” he said. “The best we can do is leverage what is going to occur — it’s unavoidable. Leverage the inevitability of well-regulated development to do the restoration that we need to do.”

It’s a philosophy that others — including some environmentalists — are beginning to appreciate for dam removals.

The Nature Conservancy recently concluded in a white paper that removing dams and culverts provide more successful mitigation than other efforts.

“If you remove a dam, you realize a lot of benefits for people and nature, and those benefits are usually enduring and sustainable,” said Jessica Wilkinson, an author of the report. “Dam removals — improving connectivity — can be and should be an appropriate method” for mitigation.

To some, mitigation represents a silver bullet for financing dam removals.

Public and private investments in compensatory mitigation is “conservatively” estimated at $3.8 billion annually, according to a widely cited 2015 paper on the “restoration economy” by University of North Carolina professor Todd BenDor. Some in the industry estimate that figure is now as high as $5 billion.

“Conceptually, it’s a great idea,” said Steven Stockton, former director of civil works and dam safety officer for the Army Corps of Engineers.

But Stockton pointed out the obstacles, the biggest being that someone’s got to foot the bill for mitigation that typically must take place in the same watershed as the development. Another is that mitigation banking has never had broad political support needed to make it a Clean Water Act fixture.

Nonetheless the number of for-profit dam removals is growing. Serena McClain of American Rivers counts about two dozen dam removals for mitigation and nine others under consideration.

Annapolis, Md.-based GreenVest LLC, another mitigation firm, has been behind removals in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland.

“It should be considered more often,” said Doug Lashley, GreenVest’s CEO.

Dam removal for mitigation also appears to be a rare example of environmental work that has bipartisan appeal.

Greens see rivers restored. Republicans see a market-driven solution, sort of akin to the acid rain cap-and-trade Clean Air Act program.

“In a way, this is a Rosetta stone,” said Mike Wicker of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in North Carolina. “Biologists like me see the strong environmental uplift. And it’s a mechanism for guys in the private sector to make some money.”

Howard encapsulates that dynamic.

The 51-year-old has worked for two North Carolina Republican senators, Jesse Helms and Lauch Faircloth. In the mid 1990s, Howard spearheaded unsuccessful legislation from Faircloth, who sat on the Environment and Public Works Committee, to deregulate wetlands.

But Howard’s no fan of the Trump administration’s efforts to rescind the Obama administration’s Clean Water Rule — also known as Waters of the U.S., or WOTUS — which defines what marshes, streams and wetlands qualify for federal protections.

He calls the current administration “regulatory barbarians.”

“Our business depends on well-regulated environments,” he said.

Howard sensed an opportunity in the then-fledgling mitigation banking industry while working on the wetlands bill. He returned to North Carolina and launched Restoration Systems.

“It was a dramatic departure from my career,” he said. “I went from wearing Brooks Brothers suits to Carhartt pants in 90 days.”

So far, all dam removals for mitigation have occurred in the East. But many, like Howard, see potential across the country.

“The East is more obvious because the rivers are smaller, the dams are smaller and they are all really obsolete,” said former Interior Secretary and Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt (D). “But there is plenty of work out here, too.”

If it’s successful, Fish and Wildlife’s Wicker believes the removal of the century-old Milburnie Dam will become a model.

“Milburnie is right on the edge of Raleigh,” he said. “That’s what the system is waiting for — to see if this will work for one of these contentious dams.”

‘Uplift’

Neuse River dams. The Neuse River, North Carolina’s longest, has seen a series of dam removals since the late 1990s. After the Milburnie Dam is removed, nearly 250 miles of the river will flow unimpeded. Claudine Hellmuth/E&E News

The Neuse River rises in central North Carolina’s rocky Piedmont region, winds about 275 miles east, past Raleigh, before becoming the nation’s widest river — 6 miles across — as it drains into Pamlico Sound.

It is the state’s longest river and home to several dams that generated power for paper and corn mills, Raleigh’s street cars and various other purposes. Some of the dams stretch back two centuries, and almost all of them are useless now, leading to a spree of removal projects.

In 1998, Interior Secretary Babbitt visited the area to celebrate the removal of Quaker Neck Dam near Goldsboro. Though only 17-feet tall, the impoundment effectively cut the Neuse in half for fish when it was built in 1952. Obliterating it restored about 78 miles of the Neuse main stem to migratory fish like shad and striped bass, as well as some 900 miles of its tributaries.

The same year, the nearby Cherry Hospital Dam was also taken out. Rains Mill Dam, upstream on a tributary, came out the following year.

Mike Wicker. Photo credit: Wicker/Special to E&E News

Around that time, North Carolina launched a Dam Removal Task Force comprising state and federal agencies.

Each agency examined the state’s more than 5,600 dams and evaluated them based on various priorities — ecology, public safety, transportation and others.

Dams were given numerical values. In 2002, the state released a top 10 list of dams that should be taken out.

During that process, Wicker, the veteran FWS biologist, had an idea. What if dam removal could be used for compensatory mitigation? North Carolina, and particularly the Raleigh area, were growing rapidly, spawning development that was heavily affecting streams and wetlands.

Wicker thought dam removals would have a more lasting impact than traditional mitigation measures, which he characterized as “hard engineering” that generate an artificial landscape requiring perpetual maintenance.

“Generally with mitigation, the environment sort of gets the short end of the stick,” Wicker said.

Wicker thought using dam removals for compensatory mitigation could be a “magic key.”

“I thought this technique would be a way of really getting some uplift, not only adequate mitigation, but some bonuses,” he said.

The concept grabbed Howard’s attention. Seven of the top 10 dams on the state list have since been removed. In total, 30 dams in North Carolina have been torn down, including eight in 2016 alone, according to data from American Rivers.

Howard’s Restoration System tore down two of the Top 10: Lowell Dam in a tributary of the Neuse and Carbonton Dam on the Deep River in 2005.

Construction crews work to dismantle Milburnie dam. Photo credit: Restoration Systems

The state and cities bought the mitigation credits generated by both removals, paying Howard’s company $4.8 million for the credits from Lowell’s removal, and $12 million for those from Carbonton.

Howard said it appeared that the idea would catch on then. He has been working to remove the privately owned Milburnie Dam, the last small dam on the Neuse River and another on the state’s Top 10 list, since 2001. His company will ultimately spend more than $2 million tearing it down.

“We had great hopes for it in the mid-2000s when we took out the first two,” he said. “The agencies have been slow to catch up.”

‘This should be a win-win’

That doesn’t mean U.S. EPA and the Army Corps haven’t tried.

The Army Corps’ Wilmington District and EPA Region 4 have sought to be leaders on the issue. Beginning in 2003, the agencies have twice issued guidance “to provide a consistent method to determine mitigation credit derived from appropriate dam removal projects across North Carolina.”

“We all got together back in the early 2000s because the development pressure was so great here,” said Jean Gibby, chief of the Army Corps’ Raleigh regulatory office.

Then, in April 2008, the Obama administration issued a regulation that stated a clear preference for mitigation banking over other types of compensatory mitigation under the Clean Water Act.

A prime motivation for the rule was the main form of mitigation previously — in which the permit seeker does some sort of project on their own — wasn’t working, said Royal Gardner, a law professor at Stetson University who has written extensively on the Clean Water Act.

“It was clear that permittee responsible mitigation was not successful,” Gardner said.

Proponents of mitigation banking contend there are advantages both for the permit seeker and the regulator. For the developer, it is easier to buy credits from a bank than undertake an entire mitigation project. The credits also release them from the liability of making sure the project is successful over the long term. For the Milburnie Dam bank, for example, Howard’s company will monitor the site for seven years.

At the same time, the regulator knows the credits are bought from a bank that it has evaluated and deemed worthy.

It’s the type of regulation that pro-business conservatives support.

“This is an area with the proper amount of policy and guidance from the federal government pushed down districts” could lead to “a lot of dams being removed and providing compensatory mitigation,” said Murray Starkel of Ecological Service Partners, another mitigation banker who sees potential for dam removal banks in the Pacific Northwest.

“This should be a win-win.”

The Obama administration rule boosted the mitigation bank market for stream restoration, according to the Nature Conservancy white paper. The number of mitigation banks across the country providing stream mitigation credits jumped from 141 in 2008 to more than 300 in 2014.

Both 2008 efforts have since encountered challenges.

The North Carolina guidance has been repeatedly withdrawn, most recently in 2011, in part due to resistance from traditional stream mitigation companies.

“It scared people because it was precedent-setting and different,” Wicker saidThe Army Corps’ Gibby said the document was rescinded largely due to technical issues, including difficulty reconciling it with the national mitigation rule.

“Like anything, when you first do something you are going to find that it’s not perfect the first time,” she said.

That Obama-era rule is also now in jeopardy; the Trump administration has listed it as one it will re-evaluate and possibly repeal.

Mitigation bankers also say regulators approve projects much more quickly than banks.

‘Neither side agrees with it’

The 15-foot high, 625-foot wide Milburnie Dam before it was removed. More than 100 years old, the dam creates dangerous hydraulic suction and has drowned 15 swimmers.

Overall, mitigation banking has never had a large contingent of political backers in either party, Howard said.

Many conservatives don’t like it because they don’t agree with federal regulations, while many greens are suspicious of it as a potential spur for development.

“Mitigation banking is good policy, but it has never had a lover,” Howard said. “That’s a hell of a policy if neither side agrees with it. But that means it’s a good policy.”

Matthew Starr of the Upper Neuse Riverkeeper acknowledged that mitigation banking is “a little bit of a Catch-22.”

“In a perfect world, you wouldn’t need mitigation. It would be removed because that’s what’s best for the environment and the public,” he said.

But, he added, “in any political climate this is necessary because it’s the only way it’s going to be done.”

Wicker, the folksy FWS biologist, turned metaphoric when asked the significance of the Milburnie Dam removal.

“A blind hog finds an acorn every now and then,” he said. “I think we are about to eat a great big acorn.”