Expect waterways flush with migratory fish once outdated dams are dust

Expect waterways flush with migratory fish once outdated dams are dust

Wade Rawlins

Staff Writer

Three blasts of dynamite turned the 10-foot-thick Lowell Dam into a crazed wall of concrete rubble that backhoes began scooping away this week.

Soon, the Little River will return to a shallow, rock-riffled waterway that feeds the Neuse. And by spring, migratory fish such as shad, herring and striped bass will have free passage from the Atlantic Ocean up the Little River and Buffalo Creek almost to Wake County.

The Lowell Dam, near Kenly in Johnston County, is the fourth dam on the Neuse and Little rivers to fall since 1998 in an effort to restore free-flowing waters in the river basin and reopen historic spawning grounds.

For species such as herring, greater areas for spawning means a chance to reverse declining populations. More abundant fish means more opportunity for people who enjoy catching and eating them and for commercial fishermen who depend on catches to make a living.

"It’s the first time since 1810 that [migratory] fish have been able to pass this far upstream into the Piedmont," said George Howard, co-founder of Restoration Systems, a Raleigh company that specializes in environmental restoration and undertook the dam removal.

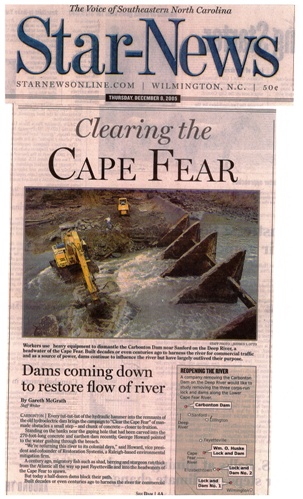

Nearby, at the border of Lee, Chatham and Moore counties, another outdated impoundment, the Carbonton Dam, is coming down to restore habitat for the Cape Fear shiner, a small endangered minnow. The fish is found only in a few places in the Deep River and other tributaries of the Cape Fear River.

Dam removals restore habitat for aquatic species. In coming months, on the newly exposed mud flats behind Lowell Dam, restoration crews will roll out mats of coconut fiber seeded with rye grass and plant trees there to stabilize the river banks.

New role in river’s life

Gary Scott, 33, a Johnston County farmer whose family once owned the dam, stood on the bank watching the yellow backhoes scoop up chunks of concrete. Scott said the structure had served its purpose powering a mill to grind grain, and its removal was good for the environment.

"It will give the folks upstream a chance to catch some of these shad that we have been hogging," Scott said.

Scott said he had seen thousands of shad gathered at the Lowell Dam each spring — blocked by the structure from swimming further. The fish had made their way to the Lowell Dam only since 1999, when the Rains Mill Dam downstream near Princeton was removed.

"You can come down here in early spring, and people are just lined up here fishing," he said. "There are people trying to catch them by hand."

Historically, the Neuse River and its tributaries produced more American shad than any other river in the state. The dams have been a barrier to the spring spawning run of the species, which has declined dramatically in commercial catches. Large migrations of American shad are expected to occur next spring in the stretch of river above the Lowell Dam.

Tim Savidge, an aquatic biologist with the Catena Group, an environmental consulting company involved in the project, said removing the dam should provide more suitable habitat not only for fish, but for several species of endangered mussels. The dwarf-wedge mussel and Tar River spinymussel are among those that will benefit. Some species of freshwater mussels attach themselves to fish gills to move about as part of their reproduction process.

Before the demolition, Savidge and several divers were tagging mussels buried in the river bottom near the dam. They’ll survey the mussels in months ahead to determine how the dam’s removal has affected them and whether they’ve been choked by sediment moving downstream.

Since the removal of the Rains Mill Dam in 1999, Savidge said he had found species of mussels that had been found only below the dam beforehand, indicating they were expanding their presence in the river. He expects to observe a similar pattern after this dam removal.

"Just a simple thing like changing the speed at which a river flows changes the aquatic habitat," said Adam Riggsbee, a graduate student in environmental sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who is doing research on the dam removals.

Both the Lowell and Carbonton dams were on a list of small dams compiled by state and federal agencies in 2002 that would benefit the environment by being removed. Other high-priority removals are two dams on the Cape Fear.

"We’re not trying to look at all dams and say they are bad," said Mike Wicker, a biologist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. "We do think there are a small number of dams in North Carolina that are extremely bad for the environment. We’re trying to ferret out the ones that are atrocities for the environment and get rid of those."

Federal laws such as the Clean Water Act require a trade-off when development or highway construction harms the environment. The harm must be offset by an environmental good deed, such as a stream restoration or dam removal.

Ecological ‘credits’

But the state doesn’t actually have to do the restoration work itself. Instead, it can purchase "credits" from someone else who has done environmental restoration work.

Restoration Systems purchased the Lowell Dam, then won a $4.3 million state contract to sell its conservation credits generated by the removal. It is also removing the Carbonton Dam.

The state will use the credits to compensate for disturbance caused by state highway projects such as Raleigh’s Outer Loop. The number of credits is based on the length of the river that is restored by removing the dam.

"The Outer Loop is driving the removal of this dam and restoration of this river," Restoration’s Howard said.

Restoration Systems also plans to donate 17 acres for a public park and provide $140,000 as an endowment to maintain the park.

"The question is, what do we want our world to look like?" Howard said. "People have stated a strong preference to policy-makers that, ‘We want our world to bear some resemblance to that which we once knew.’ That includes fish and mussels."

Staff writer Wade Rawlins can be reached at 829-4528 or wrawlins@newsobserver.com.