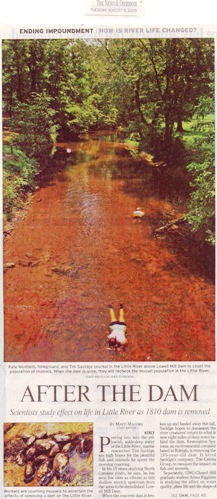

KENLY — Peering into into the yellowish, ankle-deep water of the Little River, marine researcher Tim Savidge has high hopes for the plentiful fish and mussels he spent the morning counting.

In his 15 years studying North Carolina rivers, he says, he has seen few sites as vibrant as this shallow stretch upstream from the soon-to-be-demolished Lowell Mill Dam.

When the concrete dam is broken up and hauled away this fall, Savidge hopes to document the river creatures’ return to what is now eight miles of deep water behind the dam. Restoration Systems, an environmental company based in Raleigh, is removing the 195-year-old dam. It hired Savidge’s company, The Catena Group, to measure the impact on fish and mussels.

Separately, UNC-Chapel Hill graduate student Adam Riggsbee is studying the effect on water quality, plant life and the shape of the riverbed.

Scientists hope the lessons learned at Lowell Mill will apply to a handful of dam removal projects in North Carolina and others throughout the United States.

"It will really expedite the removal of the dams that need to be removed and will educate us on which ones it would be a benefit to remove," said Mike Wicker, a biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Raleigh. "It will answer very decidedly some of the questions about how rivers respond to dam removal."

Is removal helpful?

Most of those questions revolve around whether a river actually benefits when a dam is removed.

The pace of dam removals nationwide quickened in the 1990s as many dams outlived their intended purposes. Nearly 200 dams were removed in that decade, according to the International Rivers Network, a nonprofit that promotes dam removal.

Like the Lowell Mill Dam, many of North Carolina’s 5,000 dams were built to power gristmills and are no longer in use. Proponents say removing them allows migratory fish to return to the rivers where they used to spawn.

But research has been slow to back up the environmental benefits. Most of the research has taken place in the Midwest, where dams are more often removed for safety reasons than environmental ones.

Researchers at N.C. State University have proved that ocean-dwelling fish will return to rivers after dams are removed. But they haven’t shown that the overall health of the river improves, Wicker said. Nor have they documented the return of mussels, which improve water quality by filtering out pollutants.

If conditions improve on the Little River, the demolition of three massive lock-and-dams along the Cape Fear River between Wilmington and Fayetteville might speed up.

A test case

The removal of two dams on the Little and Neuse rivers has allowed shad and sturgeon to reach the Lowell Mill Dam, a simple concrete wall that spans the Little River near Interstate 95. The dam, built in 1810, raised the level of the river as much as 11 feet.

For his doctoral dissertation in environmental science, Riggsbee is tracking how plant life returns to the riverbed as the water recedes. He is also monitoring nutrients in the soil and water to see whether the area returns to its natural state.

In April, he and a dozen other students stayed at the dam all night to take water samples as water began to flow freely past the dam for the first time.

Back in Chapel Hill, Riggsbee keeps a greenhouse where he can simulate floods both before and after the dam’s removal.

As the water level recedes, rains will infuse the river with sudden bursts of nutrients that could be too much for some plants and animals.

"You can go too far with nutrients," Riggsbee said. "It’s like that last drink when you know you’ve had too many."

Restoration Systems has taken a gamble on buying and removing the Lowell Mill Dam, said co-founder George Howard.

The for-profit company will earn mitigation credits from the state for improving the environment there. It can sell the credits to developers who must compensate for felling trees or paving wetlands.

To get the credits, Restoration Systems must prove that fish and mussel populations increase after the dam is removed this fall.

Savidge and his team are counting mussels and fish so that they can compare their numbers after the dam is gone. So far, they have found many more mussels, including the endangered dwarf wedge and Tar spiny mussels, outside the impounded area.

Howard and his crew have been slowly lowering the water levels of the Little River for 18 months. Now, he said, it is almost as low as it will be when the dam is removed.

Locals aren’t all pleased about the change.

Power boats will no longer be able to use the river, and newly exposed logs make it unsightly and hard to navigate even in a canoe.

Howard said his company plans to clean up the river. The company is also giving Johnston County 17 acres near the dam for a park, along with a $140,000 endowment for its upkeep.

Riggsbee said local controversies over dam removal contribute to the dearth of research, because scientists are leery of projects that may fall through. He hopes his research will tip the scales on other projects.

"There’s a lot of hesitation to do it," he said. "No one really knows what removing a dam does. The rest of the state will look at what I’m doing and a few other researchers and evaluate if this is a good idea."

By Marti Maguire

Staff Writer