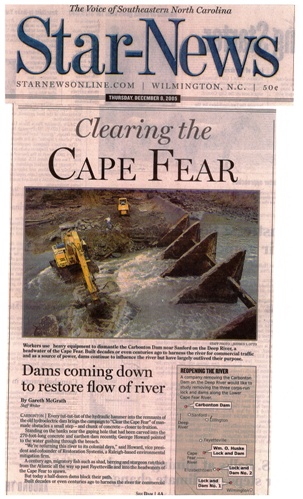

CARBONTON — Every tut-tut-tut of the hydraulic hammer into the remnants of the old hydroelectric dam brings the campaign to “Clear the Cape Fear” of manmade obstacles a small step – and chunk of concrete – closer to fruition.

CARBONTON — Every tut-tut-tut of the hydraulic hammer into the remnants of the old hydroelectric dam brings the campaign to “Clear the Cape Fear” of manmade obstacles a small step – and chunk of concrete – closer to fruition.

By Gareth McGrath

Staff Writer

Standing on the banks near the gaping hole that had been carved into the 270-foot-long concrete and earthen dam recently, George Howard pointed to the water gushing through the breach.

“We’re returning this river to its colonial days,” said Howard, vice president and cofounder of Restoration Systems, a Raleigh-based environmental mitigation firm.

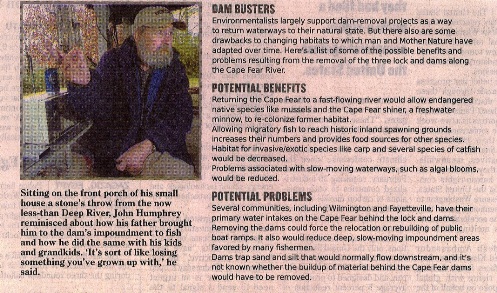

A century ago, migratory fish such as shad, herring and sturgeon ran thick from the Atlantic all the way up past Fayetteville and into the headwaters of the Cape Fear to spawn.

But today a half-dozen dams block their path.

Built decades or even centuries ago to harness the river for commercial traffic and as a source of power, the dams continue to influence the Cape Fear even as they have largely outlived their purpose.

The three locks run by the Army Corps of Engineers along the Lower Cape Fear, for example, are now opened only to provide passage to migratory fish. The commercial traffic they were built to serve dried up long ago, and recreational boats have slowed to a trickle.

Restoration Systems wants to change that by removing most of the structures – including possibly all three of the lock and dams.

The roughly $8.2 million dam-removal project here along the Deep River, one of the river’s headwaters, offers a blueprint as to how the company would approach the Cape Fear facilities.

Howard said the two upper lock and dams, both in Bladen County, were ranked among the five dams whose removal would be most beneficial to the environment by the N.C. Dam Removal Task Force. The group is a multi-agency group looking at dams that pose problems for the environment.

“There’s been a tremendous amount of damage done to that river, and we see abundant restoration opportunities along the Cape Fear,” he said.

Biologists agree.

“I don’t think there’s any question that the dams are a tremendous break on the river’s ability to produce fish,” said Mike Wicker, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Raleigh office. “Here we have a potentially very productive system that’s being denied this productivity by these dams.”

An act of Congress

But there are plenty of rapids to navigate before heavy equipment could begin dismantling the structures. Regulatory and operational issues must be tackled. It would literally require an act of Congress.

Corps officials have said the agency can’t just turn the proverbial keys to the locks over to the private sector – even though the agency has been pushing for years to get out of the Cape Fear dam business.

“The bottom line is they are an authorized project, and before we or anybody else can do anything to them they have to be de-authorized, and that requires an act of Congress,” said corps biologist Frank Yelverton. “And we can’t go to Congress until we have a report.”

The corps is reviewing its mitigation requirements for the ongoing Wilmington Harbor Deepening project, which could include a recommendation on the fate of the lock and dams.

Some eyebrows also have been raised about Restoration System’s zeal to invest its time and money to remove the dams. The Carbonton project is the first dam removal in North Carolina primarily for mitigation purposes.

Howard doesn’t deny that his company is in the dam-removal business to make a profit. The Carbonton project will generate mitigation credits for the N.C. Department of Transportation and Siler City.

But he said the concept makes development a driver – instead an enemy – of conservation.

“On the one hand, we’re helping growth,” Howard said. “On the other hand, we’re re-growing resources that were lost a long time ago.

“We really do see it as a win-win proposition.”

Stagnant waters

The Carbonton Dam, tucked into this quiet corner of the hilly Sandhills equidistant from Raleigh, Fayetteville and Greensboro, wasn’t in good shape before the heavy equipment moved in last week.

“It was basically an abandoned dam,” Howard said, ticking off a slew of safety and structural problems.

The 17-foot-high dam, which was built in 1921, is the latest in a series of dams that has sought to harness this stretch of the Deep River.

But man’s push to control nature has remade nearly 11 miles of waterway above the dam.

From a free-flowing river, the Deep has turned into a slow-moving waterway that has lost many of its natural characteristics.

Instead of native mussels and a stable population of Cape Fear shiner, an endangered freshwater minnow, the largely stagnant stretch of river became home to catfish, carp and bass.

“There are a lot of fish species up there, but not what would be in there naturally,” said Ryan Heise, a biologist with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission.

The dam also blocked the flow of material downstream, leaving a mass of material wedged against the structure.

“The downstream part of this river is sediment-starved, which would be the same case in the Cape Fear River,” Howard said as a backhoe removed a picnic table-size chunk of concrete from the broken dam.

A changed environment

But removing a dam isn’t as simply as hauling heavy equipment into a river or using a few sticks of dynamite.

The areas above the Cape Fear’s lock and dams, as above the Carbonton Dam, have adapted to the new environment.

They also have become recreational draws, providing important economic boosts to rural communities that don’t have a lot else going for them.

The impoundment areas behind the dams also are home to the water intakes for several communities in the watershed, including Wilmington and Fayetteville.

Howard said his company is sensitive to the needs and concerns of the community and would work with all stakeholders to mitigate any problems caused by the dam removal.

“This would be a fairly complex arrangement, and one that could take a lot of work on both sides,” he said. “But the essential proposal is fairly straightforward.”

For instance, the company plans to give the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission $20,000 to replace or modify a boat ramp that’s been left dry just above the Carbonton Dam as water levels have fallen. The old dam site also will be turned into a public park.

Howard also said that dam removal isn’t a process that happens overnight. The Carbonton Dam removal is a 10-year project, with half of that dedicated to environmental monitoring after the dam is removed.

Heise, the state biologist, also cautioned about rushing into any removal project.

“You have to look at what ecological benefits are you going to obtain and at what cost, and some of the time it’s very clear,” he said. “At Carbonton, it was a no-brainer. But these types of projects need to be looked at on a case-by-case basis.”

While any possible action on the corps’ lock and dams is probably years off, the seed has been planted for their removal.

Howard said he’s already broached the idea with officials in Washington and Raleigh and received positive feedback.

But he understands that not everyone will be happy to see the dams go.

Sitting on the front porch of his small house a stone’s throw from the now less-than Deep River, John Humphrey reminisced about how his father brought him to the dam’s impoundment to fish and how he did the same with his kids and grandkids.

“It’s sort of like losing something you’ve grown up with,” he said, the thump of the hydraulic hammer echoing through the tree-covered hills. “But if there’s a reason for it, OK.

“But a lot of people around here are going to miss it.”