Company putting new life in Lick Creek

SANFORD – A Raleigh-based environmental restoration firm working to redirect Lick Creek northeast of Sanford recently discovered animal life in the creek and is making efforts to preserve as much of it as possible.

SANFORD – A Raleigh-based environmental restoration firm working to redirect Lick Creek northeast of Sanford recently discovered animal life in the creek and is making efforts to preserve as much of it as possible.

By Gordon Anderson

Staff Writer

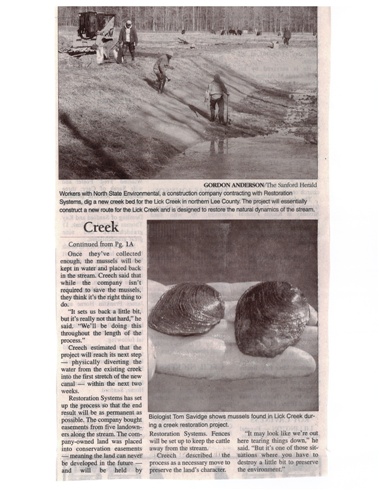

Restoration Systems, LLC is performing a restoration project on 9,500 feet of the Lick Creek, which crosses Lower Moncure Road near Riddle Road. The company is rerouting parts of the stream, which currently runs more or less in a straight line, by digging a new canal and adding several bends.

Worth Creech, the project’s manager, said the restoration was necessary because various factors – including cattle getting into the stream and eroding the banks, typical aging and even construction on the nearby U.S. 421 bypass project – were leading to the wearing down of the stream, which runs through several rural residential and agricultural tracts.

Creech said that last week, however, biologists working for Restoration Systems discovered four species of mussels living in the banks of the stream. Although none of the mussel species are endangered – and Restoration Systems is not required to save them – Creech said he and others involved in the projects are saving them anyway.

Creech, along with biologists Randy Turner and Tim Savidge, spent Friday wading through the stream and picking up mussels by hand. The expedition was the second of its type, and Creech said he expects to make at least three or four more trips to collect mussels.

Once they’ve collected enough, the mussels will be kept in water and placed back in the stream. Creech said that while the company isn’t required to save the mussels, they think it’s the right thing to do.

“It sets us back a little bit, but it’s really not that hard,” he said. “We’ll be doing this throughout the length of the process.”

Creech estimated that the project will reach its next step – physically diverting the water from the existing creek into the first stretch of the new canal – within the next two weeks.

Restoration Systems has set up the process so that the end result will be as permanent as possible. The company bought easements from five landowners along the stream. The company-owned land was placed into conservation easements – meaning the land can never be developed in the future – and will be held by Restoration Systems. Fences will be set up to keep the cattle away from the stream.

Creech described the process as a necessary move to preserve the land’s character.

“It may look like we’re out here tearing things down,” he said. “But it’s one of those situations where you have to destroy a little bit to preserve the environment.”

Firm Proposes Removal of Cape Fear Dams

Restoration Systems Performing Similar Work in Carbonton, NC

Restoration Systems Performing Similar Work in Carbonton, NC

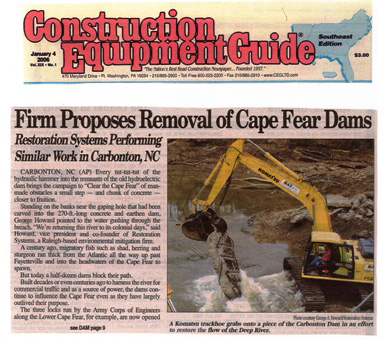

CARBONTON, NC (AP) Every tut-tut-tut of the hydraulic hammer into the remnants of the old hydroelectric dam brings the campaign to “Clear the Cape Fear” of manmade obstacles a small step — and chunk of concrete — closer to fruition.

Standing on the banks near the gaping hole that had been carved into the 270-ft.-long concrete and earthen dam, George Howard pointed to the water gushing through the breach. “We’re returning this river to its colonial days,” said Howard, vice president and co-founder of Restoration Systems, a Raleigh-based environmental mitigation firm.

A century ago, migratory fish such as shad, herring and sturgeon ran thick from the Atlantic all the way up past Fayetteville and into the headwaters of the Cape Fear to spawn.

But today a half-dozen dams block their path.

Built decades or even centuries ago to harness the river for commercial traffic and as a source of power, the dams continue to influence the Cape Fear even as they have largely outlived their purpose.

The three locks run by the Army Corps of Engineers along the Lower Cape Fear, for example, are now opened only to provide passage to migratory fish. The commercial traffic they were built to serve dried up long ago, and recreational boats have slowed to a trickle.

Restoration Systems wants to change that by removing most of the structures, including possibly all three of the lock and dams.

Carbonton Project Similar

The roughly $8.2 million dam-removal project here along the Deep River, one of the river’s headwaters, offers a blueprint as to how the company would approach the Cape Fear facilities.

The Carbonton Dam, constructed in 1921, has not been used to generate electricity for nearly a year-and-a-half, said Project Manager Randy Turner.

Work began in the fall, but has mostly centered around clearing regulatory hurdles.

“We haven’t had any difficulties with any of the agencies, it has just taken awhile to go through the process,” Turner said.

Workers have completed some grading of the substrate areas.

In addition, crews dewatered the structure slowly to reduce the stress on waterlife downstream. During the dewatering process, crews discovered their colleagues who built the dam 90-some years ago left the old timber cofferdam structures in place, which trapped sediment behind

Turner said the contractor, Backwater Environmental of Pittsboro, NC, will rely on tracked equipment when the dismantling of the dam structure begins, as it makes it easier to get around a riverbed. Trackhoes will demolish the structure and tracked hopper trucks will haul the material — approximately 1,500 cu. yds. of concrete, plus some tree debris — from the river onto dry land.

No wetlands are associated with the Deep River, so Turner expects to haul the material away from the site with rubber-tired trucks. It will be buried off-site.

The Carbonton Dam, tucked into this quiet corner of the hilly Sandhills equidistant from Raleigh, Fayetteville and Greensboro, wasn’t in good shape before the heavy equipment moved in.

“It was basically an abandoned dam,” Howard said, ticking off a slew of safety and structural problems. The 17-ft.-high dam, which was built in 1921, is the latest in a series of dams that has sought to harness this stretch of the Deep River.

But man’s push to control nature has remade nearly 11 mi. of waterway above the dam.

From a free-flowing river, the Deep has turned into a slow-moving waterway that has lost many of its natural characteristics. Instead of native mussels and a stable population of Cape Fear shiner, an endangered freshwater minnow, the largely stagnant stretch of river became home to catfish, carp and bass.

“There are a lot of fish species up there, but not what would be in there naturally,” said Ryan Heise, a biologist with the NC Wildlife Resources Commission. The dam also blocked the flow of material downstream, leaving a mass of material wedged against the structure.

“The downstream part of this river is sediment-starved, which would be the same case in the Cape Fear River,” Howard said as a trackhoe removed a picnic table-size chunk of concrete from the broken dam.

Turner said that with a low river level and a recent lack of rain, crews are now at a point where they can begin the major part of the demolition work. He expects the job will be completed by the end of January.

Work Would Restore River

Howard said the two upper lock and dams, both in Bladen County, were ranked among the five dams whose removal would be most beneficial to the environment by the NC Dam Removal Task Force. The group is a multi-agency group looking at dams that pose problems for the environment.

“There’s been a tremendous amount of damage done to that river, and we see abundant restoration opportunities along the Cape Fear,” he said.

Biologists agree.

“I don’t think there’s any question that the dams are a tremendous break on the river’s ability to produce fish,” said Mike Wicker, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Raleigh office. “Here we have a potentially very productive system that’s being denied this productivity by these dams.”

But there are plenty of rapids to navigate before heavy equipment could begin dismantling the structures. Regulatory and operational issues must be tackled. It would literally require an act of Congress.

Corps officials have said the agency can’t just turn the proverbial keys to the locks over to the private sector — even though the agency has been pushing for years to get out of the Cape Fear dam business.

“The bottom line is they are an authorized project, and before we or anybody else can do anything to them they have to be de-authorized, and that requires an act of Congress,” said corps biologist Frank Yelverton.

“And we can’t go to Congress until we have a report.”

The corps is reviewing its mitigation requirements for the ongoing Wilmington Harbor Deepening project, which could include a recommendation on the fate of the lock and dams.

Some eyebrows also have been raised about Restoration System’s zeal to invest its time and money to remove the dams. The Carbonton project is the first dam removal in North Carolina primarily for mitigation purposes.

Howard doesn’t deny that his company is in the dam-removal business to make a profit. The Carbonton project will generate mitigation credits for the NC Department of Transportation and Siler City. But he said the concept makes development a driver instead an enemy of conservation.

“On the one hand, we’re helping growth,” Howard said. “On the other hand, we’re re-growing resources that were lost a long time ago. “We really do see it as a win-win proposition.”

But removing a dam isn’t as simply as hauling heavy equipment into a river or using a few sticks of dynamite.

The areas above the Cape Fear’s lock and dams, as above the Carbonton Dam, have adapted to the new environment.

They also have become recreational draws, providing important economic boosts to rural communities that don’t have a lot else going for them.

The impoundment areas behind the dams also are home to the water intakes for several communities in the watershed, including Wilmington and Fayetteville. Howard said his company is sensitive to the needs and concerns of the community and would work with all stakeholders to mitigate any problems caused by the dam removal.

“This would be a fairly complex arrangement, and one that could take a lot of work on both sides,” he said. “But the essential proposal is fairly straightforward.”

For instance, the company plans to give the NC Wildlife Resources Commission $20,000 to replace or modify a boat ramp that’s been left dry just above the Carbonton Dam as water levels have fallen. The old dam site also will be turned into an 8-acre public park.

Howard also said that dam removal isn’t a process that happens overnight. The Carbonton Dam removal is a 10-year project, with half of that dedicated to environmental monitoring after the dam is removed.

Heise, the state biologist, also cautioned about rushing into any removal project. “You have to look at what ecological benefits are you going to obtain and at what cost, and some of the time it’s very clear,” he said. “At Carbonton, it was a no-brainer. But these types of projects need to be looked at on a case-by-case basis.”

While any possible action on the corps’ lock and dams is probably years off, the seed has been planted for their removal.

Howard said he’s already broached the idea with officials in Washington and Raleigh and received positive feedback.

But he understands that not everyone will be happy to see the dams go. Sitting on the front porch of his small house a stone’s throw from the now less-than Deep River, John Humphrey reminisced about how his father brought him to the dam’s impoundment to fish and how he did the same with his kids and grandkids.

“It’s sort of like losing something you’ve grown up with,” he said, the thump of the hydraulic hammer echoing through the tree-covered hills. “But if there’s a reason for it, OK. But a lot of people around here are going to miss it.”

CEG contributed to this report.

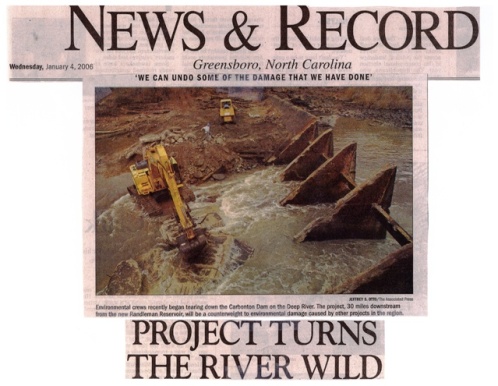

Project Turns the River Wild

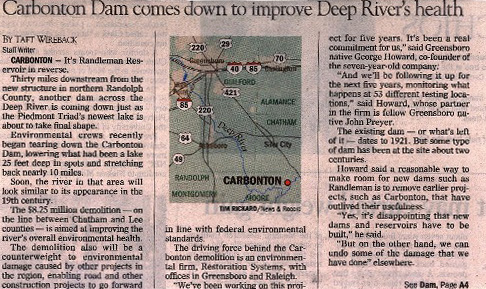

CARBONTON — It’s Randleman Reservoir in reverse.

CARBONTON — It’s Randleman Reservoir in reverse.

Taft Wireback

Staff Writer

Thirty miles downstream from the new structure in northern Randolph County, another dam across the Deep River is coming down just as the Piedmont Triad’s newest lake is about to take final shape.

Environmental crews recently began tearing down the Carbonton Dam, lowering what had been a lake 25 feet deep in spots and stretching back nearly 10 miles.

Soon, the river in that area will look similar to its appearance in the 19th century.

The $8.25 million demolition — on the line between Chatham and Lee counties — is aimed at improving the river’s overall environmental health. It also will be a counterweight to environmental damage caused by other projects in the region, enabling road and other construction projects to go forward in line with federal environmental standards.

The driving force behind the Carbonton demotion is an environmental firm, Restoration Systems LLC, with offices in the Greensboro and Raleigh.

“We’ve been working on this project for five years.

It’s been a real commitment for us,” said Greensboro native George Howard, co-founder of the seven-year-old company.

“And we’ll be following it up for the next five years, monitoring what happens at 53 different testing locations,” said Howard, whose partner in the firm is fellow Greensboro native John Preyer.

The existing dam — or what’s left of it — dates to 1921. But some type of dam has been at the site about two centuries.

Howard said a reasonable way to make room for new dams such as Randleman is to remove earlier projects that, such as Carbonton, have outlived their usefulness.

“Yes, it’s disappointing that new dams and reservoirs have to be built,” he said. “But on the other hand, we can undo some of the damage that we have done” elsewhere.

Dams are not popular with environmentalists because they disrupt a river’s natural flow, changing the kinds of water plants and creatures that can thrive. But they are needed as sources of drinking water and, in some cases, electrical power.

The demolition of Carbonton’s former hydroelectric dam is being done to accumulate environmental “offsets,” or credits, linked to successfully returning that section of the Deep to its natural, unobstructed composition.

Credits from the Carbonton project will go to the state Department of Transportation and to nearby Siler City, allowing the state to keep building or improving roads and the city to expand its existing reservoir.

Road building and reservoir expansion detract from existing streams by changing their most basic features; for example, a creek might be piped through a large culvert so a highway can be built across it. Federal law requires both public and private developers offset such damage by protecting or restoring other streams in the same, general vicinity.

Howard’s company is working with a state program, the N.C. Ecosystem Enhancement Program, which administers the resulting “stream mitigation” credits.

Just like the construction of Randleman Reservoir, the destruction of Carbonton Dam is not universally popular.

Residents of the crossroads community in southern Chatham County have grown accustomed to the lake and the recreation it provided, with depths great enough for motorboats.

“It’s just been a big fishing hole for everybody and they don’t like losing it,” said Crystal Phillips, cashier at Jim’s Cash Mart up the road from the former hydroelectric dam.

Removal will lower river levels by as much as 20 feet, turning that stretch into a stream suitable for canoes and kayaks, but no longer deep enough for motorboats.

Fish and other aquatic life will change also, meaning that such species as bass and catfish might not be as plentiful.

Project proponents say the free-flowing river will bring other recreational benefits.

The project includes a 5.5-acre, public park on the site, to be maintained by the nonprofit Triangle Land Conservancy.

The conservancy oversees several other sites on the Deep. It envisions boaters being able to put in at Carbonton and paddle to those other sites for such pursuits as hiking or picnicking, conservancy director Kevin Brice said.

“We see this as a ‘blue way’ as opposed to a green way,” Brice said of the newly emancipated river.

The dam at Carbonton was operated for years by Carolina Power & Light and, later, by a small energy company based in Burlington. But the hydroelectric operation was shut down in June 2004.

The two dams’ opposite points on the life cycle aren’t the only contrasts between Randleman Reservoir and the Carbonton project.

Experts said that building a lake at Randleman will help the environment by requiring the cleanup of several polluted sites along the river. It also will help by creating a large pool where urban and industrial pollutants can settle out or deteriorate in the slower flow, they said.

But in the rural, lower Deep River, environmental scientists said restoring the river’s natural, faster current would make the water richer in oxygen.

That would allow a native fish — the endangered Cape Fear Shiner to repopulate a stretch of river it hasn’t been able to inhabit for a long time, scientists said.

The dam was partly torn down in late November, allowing the impounded water to drain slowly and return the river to its natural level.

In the coming weeks, Restoration Systems will remove the rest of dam and, eventually, begin work on the park.

Then will come years of monitoring long-range changes in the river both underwater and along its newly exposed banks.

Howard says restoration projects like Carbonton Dam are the wave of the future because developers will continue to need environmental credits to make up for their impact on the landscape.

Contact Taft Wireback at 373-7100 or twireback@news-record.com

Finally Running Free

Small stream dams have been a part of the Eastern North Carolina scenery so long that even the old-timers can’t remember what it was like before they were built. Some powered grist mills, others produced that newfangled electricity to illuminate the homes, barns and lives of rural and small folks many decades ago. But for all the benefits they once provided, the dams environmental impact was significant.

Small stream dams have been a part of the Eastern North Carolina scenery so long that even the old-timers can’t remember what it was like before they were built. Some powered grist mills, others produced that newfangled electricity to illuminate the homes, barns and lives of rural and small folks many decades ago. But for all the benefits they once provided, the dams environmental impact was significant.

Now with the roar of dynamite and the growl of heavy equipment, more and more of the old dams are being dismantled to recreate free-flowing streams across the region. It is a project that will benefit the streams, the aquatic life that calls them home and the human visitors who like to fish, paddle or simply loaf aling their banks.

The impact of even one small dam can be far reaching. Last week crews began removing the Lowell Dam on the Little River in Johnston County. The demolition not only will return the Little River to its natural past, but Buffalo Creek, Little Buffalo Creek and Long Branch also will be opened to migrating fish for the first time in many generations.

And the fish are ready to come. One Johnston County farmer whose family once owned the Lowell Dam said thousands of shad had begun gathering each spring on the downstream side of the dam since the 1999 removal of the Rains Mill Dam furhter down-river near Princeton. Environtmentalists say that removing the Lowell Dam will open 39 miles of area streams to migratory fish.

Free-flowing water also helps flush away pollution. All-in-all, the result of opening these creeks and rivers will be a more natural and healthier environment. That’s a plus for every living thing.

Torpedo the dams!

Expect waterways flush with migratory fish once outdated dams are dust

Expect waterways flush with migratory fish once outdated dams are dust

Wade Rawlins

Staff Writer

Three blasts of dynamite turned the 10-foot-thick Lowell Dam into a crazed wall of concrete rubble that backhoes began scooping away this week.

Soon, the Little River will return to a shallow, rock-riffled waterway that feeds the Neuse. And by spring, migratory fish such as shad, herring and striped bass will have free passage from the Atlantic Ocean up the Little River and Buffalo Creek almost to Wake County.

The Lowell Dam, near Kenly in Johnston County, is the fourth dam on the Neuse and Little rivers to fall since 1998 in an effort to restore free-flowing waters in the river basin and reopen historic spawning grounds.

For species such as herring, greater areas for spawning means a chance to reverse declining populations. More abundant fish means more opportunity for people who enjoy catching and eating them and for commercial fishermen who depend on catches to make a living.

"It’s the first time since 1810 that [migratory] fish have been able to pass this far upstream into the Piedmont," said George Howard, co-founder of Restoration Systems, a Raleigh company that specializes in environmental restoration and undertook the dam removal.

Nearby, at the border of Lee, Chatham and Moore counties, another outdated impoundment, the Carbonton Dam, is coming down to restore habitat for the Cape Fear shiner, a small endangered minnow. The fish is found only in a few places in the Deep River and other tributaries of the Cape Fear River.

Dam removals restore habitat for aquatic species. In coming months, on the newly exposed mud flats behind Lowell Dam, restoration crews will roll out mats of coconut fiber seeded with rye grass and plant trees there to stabilize the river banks.

New role in river’s life

Gary Scott, 33, a Johnston County farmer whose family once owned the dam, stood on the bank watching the yellow backhoes scoop up chunks of concrete. Scott said the structure had served its purpose powering a mill to grind grain, and its removal was good for the environment.

"It will give the folks upstream a chance to catch some of these shad that we have been hogging," Scott said.

Scott said he had seen thousands of shad gathered at the Lowell Dam each spring — blocked by the structure from swimming further. The fish had made their way to the Lowell Dam only since 1999, when the Rains Mill Dam downstream near Princeton was removed.

"You can come down here in early spring, and people are just lined up here fishing," he said. "There are people trying to catch them by hand."

Historically, the Neuse River and its tributaries produced more American shad than any other river in the state. The dams have been a barrier to the spring spawning run of the species, which has declined dramatically in commercial catches. Large migrations of American shad are expected to occur next spring in the stretch of river above the Lowell Dam.

Tim Savidge, an aquatic biologist with the Catena Group, an environmental consulting company involved in the project, said removing the dam should provide more suitable habitat not only for fish, but for several species of endangered mussels. The dwarf-wedge mussel and Tar River spinymussel are among those that will benefit. Some species of freshwater mussels attach themselves to fish gills to move about as part of their reproduction process.

Before the demolition, Savidge and several divers were tagging mussels buried in the river bottom near the dam. They’ll survey the mussels in months ahead to determine how the dam’s removal has affected them and whether they’ve been choked by sediment moving downstream.

Since the removal of the Rains Mill Dam in 1999, Savidge said he had found species of mussels that had been found only below the dam beforehand, indicating they were expanding their presence in the river. He expects to observe a similar pattern after this dam removal.

"Just a simple thing like changing the speed at which a river flows changes the aquatic habitat," said Adam Riggsbee, a graduate student in environmental sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who is doing research on the dam removals.

Both the Lowell and Carbonton dams were on a list of small dams compiled by state and federal agencies in 2002 that would benefit the environment by being removed. Other high-priority removals are two dams on the Cape Fear.

"We’re not trying to look at all dams and say they are bad," said Mike Wicker, a biologist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. "We do think there are a small number of dams in North Carolina that are extremely bad for the environment. We’re trying to ferret out the ones that are atrocities for the environment and get rid of those."

Federal laws such as the Clean Water Act require a trade-off when development or highway construction harms the environment. The harm must be offset by an environmental good deed, such as a stream restoration or dam removal.

Ecological ‘credits’

But the state doesn’t actually have to do the restoration work itself. Instead, it can purchase "credits" from someone else who has done environmental restoration work.

Restoration Systems purchased the Lowell Dam, then won a $4.3 million state contract to sell its conservation credits generated by the removal. It is also removing the Carbonton Dam.

The state will use the credits to compensate for disturbance caused by state highway projects such as Raleigh’s Outer Loop. The number of credits is based on the length of the river that is restored by removing the dam.

"The Outer Loop is driving the removal of this dam and restoration of this river," Restoration’s Howard said.

Restoration Systems also plans to donate 17 acres for a public park and provide $140,000 as an endowment to maintain the park.

"The question is, what do we want our world to look like?" Howard said. "People have stated a strong preference to policy-makers that, ‘We want our world to bear some resemblance to that which we once knew.’ That includes fish and mussels."

Staff writer Wade Rawlins can be reached at 829-4528 or wrawlins@newsobserver.com.

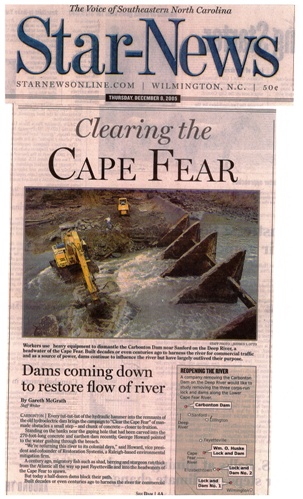

Clearing the Cape Fear: Dams coming down to restore natural flow

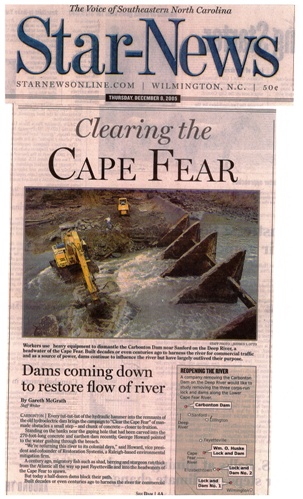

CARBONTON — Every tut-tut-tut of the hydraulic hammer into the remnants of the old hydroelectric dam brings the campaign to “Clear the Cape Fear” of manmade obstacles a small step – and chunk of concrete – closer to fruition.

CARBONTON — Every tut-tut-tut of the hydraulic hammer into the remnants of the old hydroelectric dam brings the campaign to “Clear the Cape Fear” of manmade obstacles a small step – and chunk of concrete – closer to fruition.

By Gareth McGrath

Staff Writer

Standing on the banks near the gaping hole that had been carved into the 270-foot-long concrete and earthen dam recently, George Howard pointed to the water gushing through the breach.

“We’re returning this river to its colonial days,” said Howard, vice president and cofounder of Restoration Systems, a Raleigh-based environmental mitigation firm.

A century ago, migratory fish such as shad, herring and sturgeon ran thick from the Atlantic all the way up past Fayetteville and into the headwaters of the Cape Fear to spawn.

But today a half-dozen dams block their path.

Built decades or even centuries ago to harness the river for commercial traffic and as a source of power, the dams continue to influence the Cape Fear even as they have largely outlived their purpose.

The three locks run by the Army Corps of Engineers along the Lower Cape Fear, for example, are now opened only to provide passage to migratory fish. The commercial traffic they were built to serve dried up long ago, and recreational boats have slowed to a trickle.

Restoration Systems wants to change that by removing most of the structures – including possibly all three of the lock and dams.

The roughly $8.2 million dam-removal project here along the Deep River, one of the river’s headwaters, offers a blueprint as to how the company would approach the Cape Fear facilities.

Howard said the two upper lock and dams, both in Bladen County, were ranked among the five dams whose removal would be most beneficial to the environment by the N.C. Dam Removal Task Force. The group is a multi-agency group looking at dams that pose problems for the environment.

“There’s been a tremendous amount of damage done to that river, and we see abundant restoration opportunities along the Cape Fear,” he said.

Biologists agree.

“I don’t think there’s any question that the dams are a tremendous break on the river’s ability to produce fish,” said Mike Wicker, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Raleigh office. “Here we have a potentially very productive system that’s being denied this productivity by these dams.”

An act of Congress

But there are plenty of rapids to navigate before heavy equipment could begin dismantling the structures. Regulatory and operational issues must be tackled. It would literally require an act of Congress.

Corps officials have said the agency can’t just turn the proverbial keys to the locks over to the private sector – even though the agency has been pushing for years to get out of the Cape Fear dam business.

“The bottom line is they are an authorized project, and before we or anybody else can do anything to them they have to be de-authorized, and that requires an act of Congress,” said corps biologist Frank Yelverton. “And we can’t go to Congress until we have a report.”

The corps is reviewing its mitigation requirements for the ongoing Wilmington Harbor Deepening project, which could include a recommendation on the fate of the lock and dams.

Some eyebrows also have been raised about Restoration System’s zeal to invest its time and money to remove the dams. The Carbonton project is the first dam removal in North Carolina primarily for mitigation purposes.

Howard doesn’t deny that his company is in the dam-removal business to make a profit. The Carbonton project will generate mitigation credits for the N.C. Department of Transportation and Siler City.

But he said the concept makes development a driver – instead an enemy – of conservation.

“On the one hand, we’re helping growth,” Howard said. “On the other hand, we’re re-growing resources that were lost a long time ago.

“We really do see it as a win-win proposition.”

Stagnant waters

The Carbonton Dam, tucked into this quiet corner of the hilly Sandhills equidistant from Raleigh, Fayetteville and Greensboro, wasn’t in good shape before the heavy equipment moved in last week.

“It was basically an abandoned dam,” Howard said, ticking off a slew of safety and structural problems.

The 17-foot-high dam, which was built in 1921, is the latest in a series of dams that has sought to harness this stretch of the Deep River.

But man’s push to control nature has remade nearly 11 miles of waterway above the dam.

From a free-flowing river, the Deep has turned into a slow-moving waterway that has lost many of its natural characteristics.

Instead of native mussels and a stable population of Cape Fear shiner, an endangered freshwater minnow, the largely stagnant stretch of river became home to catfish, carp and bass.

“There are a lot of fish species up there, but not what would be in there naturally,” said Ryan Heise, a biologist with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission.

The dam also blocked the flow of material downstream, leaving a mass of material wedged against the structure.

“The downstream part of this river is sediment-starved, which would be the same case in the Cape Fear River,” Howard said as a backhoe removed a picnic table-size chunk of concrete from the broken dam.

A changed environment

But removing a dam isn’t as simply as hauling heavy equipment into a river or using a few sticks of dynamite.

The areas above the Cape Fear’s lock and dams, as above the Carbonton Dam, have adapted to the new environment.

They also have become recreational draws, providing important economic boosts to rural communities that don’t have a lot else going for them.

The impoundment areas behind the dams also are home to the water intakes for several communities in the watershed, including Wilmington and Fayetteville.

Howard said his company is sensitive to the needs and concerns of the community and would work with all stakeholders to mitigate any problems caused by the dam removal.

“This would be a fairly complex arrangement, and one that could take a lot of work on both sides,” he said. “But the essential proposal is fairly straightforward.”

For instance, the company plans to give the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission $20,000 to replace or modify a boat ramp that’s been left dry just above the Carbonton Dam as water levels have fallen. The old dam site also will be turned into a public park.

Howard also said that dam removal isn’t a process that happens overnight. The Carbonton Dam removal is a 10-year project, with half of that dedicated to environmental monitoring after the dam is removed.

Heise, the state biologist, also cautioned about rushing into any removal project.

“You have to look at what ecological benefits are you going to obtain and at what cost, and some of the time it’s very clear,” he said. “At Carbonton, it was a no-brainer. But these types of projects need to be looked at on a case-by-case basis.”

While any possible action on the corps’ lock and dams is probably years off, the seed has been planted for their removal.

Howard said he’s already broached the idea with officials in Washington and Raleigh and received positive feedback.

But he understands that not everyone will be happy to see the dams go.

Sitting on the front porch of his small house a stone’s throw from the now less-than Deep River, John Humphrey reminisced about how his father brought him to the dam’s impoundment to fish and how he did the same with his kids and grandkids.

“It’s sort of like losing something you’ve grown up with,” he said, the thump of the hydraulic hammer echoing through the tree-covered hills. “But if there’s a reason for it, OK.

“But a lot of people around here are going to miss it.”

Carbonton Dam Removal

Deep River will soon go with its flow

Deep River will soon go with its flow

By Nomee Landis

Staff Writer

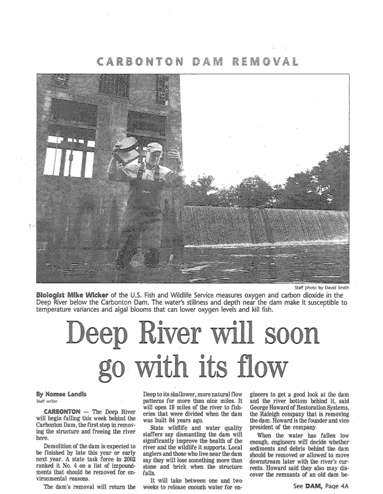

CARBONTON — The Deep River will begin falling this week behind the Carbonton Dam, the first step in removing the structure and freeing the river here.

Demolition of the dam is expected to be finished by late this year or early next year. A state task force in 2002 ranked it No. 4 on a list of impoundments that should be removed for environmental reasons.

The dam’s removal will return the Deep to its shallower, more natural flow patterns for more than nine miles. It will open 19 miles of the river to fisheries that were divided when the dam was built 84 years ago.

State wildlife and water quality staffers say dismantling the dam will significantly improve the health of the river and the wildlife it supports. Local anglers and those who live near the dam say they will lose something more than stone and brick when the structure falls.

It will take between one and two weeks to release enough water for engineers to get a good look at the dam and the river bottom behind it, said George Howard of Restoration Systems, the Raleigh company that is removing the dam. Howard is the founder and vice president of the company.

When the water has fallen low enough, engineers will decide whether sediments and debris behind the dam should be removed or allowed to move downstream later with the river’s currents. Howard said they also may discover the remnants of an old dam behind the existing one.

Once the dam is gone, Restoration Systems will build a park on the 5-acre site, on the south side of the river. The Triangle Land Conservancy will ultimately manage the park.

Restoration Systems does environmental mitigation. In this case, removing the dam will restore several miles of stream bank to its natural state. Such projects are used to compensate for the destruction of other, similar resources.

The town of Siler City plans to enlarge its dam on the Rocky River, a tributary of the Deep, to shore up drinking-water supplies. That project will destroy two miles of stream bank.

The Carbonton project is the “ideal mitigation for the loss of that resource,” Howard said. “It is not the perfect solution, but it is the best that can be arranged.”

The Carbonton project is the first of its kind, Howard said. Most stream-restoration projects involve returning channelized streams to their natural meandering states.

The demolition of the dam will lower the river level by between 13 and 16 feet, Howard said. That will make the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission boat ramp that lies just upstream unusable.

Howard said Restoration Systems is working with the commission to find an alternative ramp site. If a site is not found within 10 miles of the existing ramp, the company will pay the commission $20,000.

The park will offer a passive site where kayakers and canoeists can put their boats in the water, Howard said. Unless the water level is abnormally high, it will not be suitable for motor boats.

Something missing

Anglers who fish upstream of the dam in the lake-like stillness it creates say they will miss boating on and fishing in that deep water. And those who live around the dam say they will miss their community’s historic icon.

Gail Borg of Fayetteville has been fishing upstream of the Carbonton Dam with her husband, Jim, for years. He fishes for bass. She goes after the bream or the bluegill.

“It is so beautiful,” Gail Borg said. “The serenity is unbelievable. I will stop fishing just to look around, look at the wildlife.”

The couple uses the wildlife commission boat ramp. The dam’s demise will force them to go elsewhere, a prospect that gives them little pleasure.

“There are not many areas you can go and see what you can see and be able to fish and enjoy it,” Gail Borg said.

The Deep is a heavily dammed river. More than a dozen small hydropower dams still exist on the Deep. Construction of the Randleman Dam on the river in Randolph County was completed last year at a cost of about $85 million.

Bobby Diver grew up in the Carbonton area and raises chickens in Moore County, near the House in the Horseshoe. He does not want the dam demolished because it has been a part of the community for more than 80 years. He said a park will attract crime.

“I hate to see it taken out,” Diver said. “All it’s going to be is a little creek running through there — and a mess.”

Diver’s brother, Edward Diver, lives about a mile downstream of the dam. The river there is about 30 feet wide and knee-deep. He can still catch bass, catfish and bream in it, though.

Potential problems

In 2002, representatives of nine state and federal agencies, from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to the N.C. Division of Water Quality and the Wildlife Resources Commission, took part in the task force that ranked the dams according to their environmental effects.

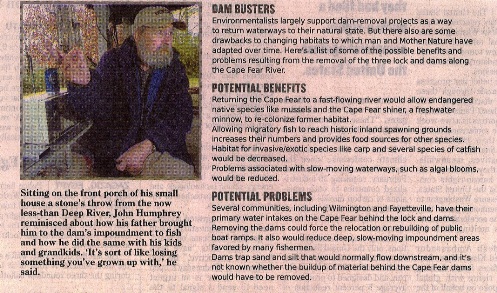

Carbonton Dam was listed because of its adverse effects on water quality in the Deep River. Near the dam, the water’s stillness and depth make it susceptible to temperature variances and algal blooms. That can lead to low oxygen levels in the water and fish kills.

Tim Savidge is an environmental supervisor with the Catena Group, a small environmental consulting firm in Hillsborough. The company performed an aquatic life survey in the river as part of the dam-removal process, in part to look for rare species.

They found them, too. They found the endangered Cape Fear shiner, a minnow that lives only in a few places in the Cape Fear River basin. That was not really a surprise, Savidge said, because it is known to live in that area of the Deep River.

Finding a granddaddy Roanoke slabshell mussel was a surprise, though.

Some mussels can survive for more than a century, Savidge said. This particular specimen, the scientists surmised, probably has been around since before the Carbonton Dam was built.

Savidge said it is believed that the Roanoke slabshell depends on an anadromous fish species for its survival. That is a fish that lives in salt water but swims up fresh-water streams to spawn.

Juvenile mussels have a parasitic relationship with their host fish species, attaching themselves to the gills of their hosts. In this way, mussels are transported throughout a river system.

The Carbonton Dam as well as other downstream dams have isolated some mussel populations, preventing their reproduction.

Removing the Carbonton Dam, Savidge said, may not be enough for the Roanoke slabshell, but about six other mussel species and more than 20 other fish species will have more room and more habitat once the dam is gone.

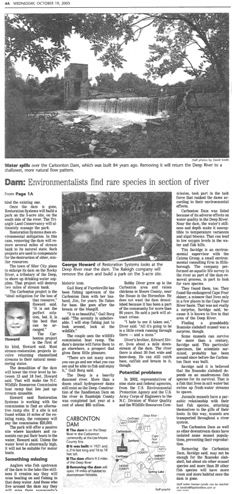

Carbonton Dam

- The dam is on the Deep River in the Carbonton community at the Lee-Moore county line.

- It was built in 1921 and is 216 feet long and 16 to 18 feet tall.

- The dam affects 9.3 miles of the Deep River.

- Removing the dam will open 19 miles of habitat to downstream fisheries.

Scientists study effect on life in Little River as 1810 dam is removed

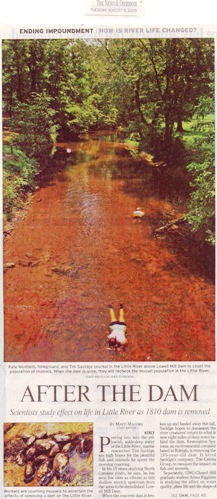

KENLY — Peering into into the yellowish, ankle-deep water of the Little River, marine researcher Tim Savidge has high hopes for the plentiful fish and mussels he spent the morning counting.

In his 15 years studying North Carolina rivers, he says, he has seen few sites as vibrant as this shallow stretch upstream from the soon-to-be-demolished Lowell Mill Dam.

When the concrete dam is broken up and hauled away this fall, Savidge hopes to document the river creatures’ return to what is now eight miles of deep water behind the dam. Restoration Systems, an environmental company based in Raleigh, is removing the 195-year-old dam. It hired Savidge’s company, The Catena Group, to measure the impact on fish and mussels.

Separately, UNC-Chapel Hill graduate student Adam Riggsbee is studying the effect on water quality, plant life and the shape of the riverbed.

Scientists hope the lessons learned at Lowell Mill will apply to a handful of dam removal projects in North Carolina and others throughout the United States.

"It will really expedite the removal of the dams that need to be removed and will educate us on which ones it would be a benefit to remove," said Mike Wicker, a biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Raleigh. "It will answer very decidedly some of the questions about how rivers respond to dam removal."

Is removal helpful?

Most of those questions revolve around whether a river actually benefits when a dam is removed.

The pace of dam removals nationwide quickened in the 1990s as many dams outlived their intended purposes. Nearly 200 dams were removed in that decade, according to the International Rivers Network, a nonprofit that promotes dam removal.

Like the Lowell Mill Dam, many of North Carolina’s 5,000 dams were built to power gristmills and are no longer in use. Proponents say removing them allows migratory fish to return to the rivers where they used to spawn.

But research has been slow to back up the environmental benefits. Most of the research has taken place in the Midwest, where dams are more often removed for safety reasons than environmental ones.

Researchers at N.C. State University have proved that ocean-dwelling fish will return to rivers after dams are removed. But they haven’t shown that the overall health of the river improves, Wicker said. Nor have they documented the return of mussels, which improve water quality by filtering out pollutants.

If conditions improve on the Little River, the demolition of three massive lock-and-dams along the Cape Fear River between Wilmington and Fayetteville might speed up.

A test case

The removal of two dams on the Little and Neuse rivers has allowed shad and sturgeon to reach the Lowell Mill Dam, a simple concrete wall that spans the Little River near Interstate 95. The dam, built in 1810, raised the level of the river as much as 11 feet.

For his doctoral dissertation in environmental science, Riggsbee is tracking how plant life returns to the riverbed as the water recedes. He is also monitoring nutrients in the soil and water to see whether the area returns to its natural state.

In April, he and a dozen other students stayed at the dam all night to take water samples as water began to flow freely past the dam for the first time.

Back in Chapel Hill, Riggsbee keeps a greenhouse where he can simulate floods both before and after the dam’s removal.

As the water level recedes, rains will infuse the river with sudden bursts of nutrients that could be too much for some plants and animals.

"You can go too far with nutrients," Riggsbee said. "It’s like that last drink when you know you’ve had too many."

Restoration Systems has taken a gamble on buying and removing the Lowell Mill Dam, said co-founder George Howard.

The for-profit company will earn mitigation credits from the state for improving the environment there. It can sell the credits to developers who must compensate for felling trees or paving wetlands.

To get the credits, Restoration Systems must prove that fish and mussel populations increase after the dam is removed this fall.

Savidge and his team are counting mussels and fish so that they can compare their numbers after the dam is gone. So far, they have found many more mussels, including the endangered dwarf wedge and Tar spiny mussels, outside the impounded area.

Howard and his crew have been slowly lowering the water levels of the Little River for 18 months. Now, he said, it is almost as low as it will be when the dam is removed.

Locals aren’t all pleased about the change.

Power boats will no longer be able to use the river, and newly exposed logs make it unsightly and hard to navigate even in a canoe.

Howard said his company plans to clean up the river. The company is also giving Johnston County 17 acres near the dam for a park, along with a $140,000 endowment for its upkeep.

Riggsbee said local controversies over dam removal contribute to the dearth of research, because scientists are leery of projects that may fall through. He hopes his research will tip the scales on other projects.

"There’s a lot of hesitation to do it," he said. "No one really knows what removing a dam does. The rest of the state will look at what I’m doing and a few other researchers and evaluate if this is a good idea."

By Marti Maguire

Staff Writer

Dam project moves forward

Fetch your rod and reel. Dust off the canoe.

Within the next several months, a Raleigh company will tear down Lowell Mill dam on the Little River and turn a half-mile section of the waterway into a county park. The free low of water will bring back migratory fish – shad, herring, sturgeon and striped bass – and open up 88 square miles of new fishing territory.

On Monday, County Commissioners accepted an offer of 17 acres of land along the river and an endowment of $140,000 to maintain the property as a park.

The park will be developed by Restoration Systems, a company that restores natural areas as mitigation credits, then sells them to agencies that disrupt wetlands, streams or forest buffers.

George Howard, a partner at Restoration Systems, said work on the land would likely start in April.

A rope-and-post fence would be erected across the length of the park to create a boundary with the adjoining private property. A gravel parking lot, interpretive signs and picnic tables would be added. The work would also include some general cleaning up.

Howard said the dam would come down in the fall when temperatures cool off. “We don’t want hot, still water running down the river,” he added.

After a long discussion with designers from Skilled Fencing, Howard said that Restoration Systems has a contract to buy 17 acres from the J.F. Scott family. And he said that the land on the north side of the river, which doesn’t have a road access, joins a large tract of land already under a conservation easement.

Commissioner Ray Woodall said the county needed to move forward with the deal. The company first pitched its proposal in November.

Howard said the company would transfer ownership once the park was complete. And it would also give the county the endowment in one payment, rather than in two as earlier proposed.

The dam, built in 1810 to power a gristmill, has been a popular fishing and swimming hole. But during the past 15 years, three people have drowned – one as recently as 2000.

Johnston lays ground for park

County accepts offer of land

County commissioners accepted a company’s proposal Monday to create Johnston’s first county-owned park at the site of the Lowell Mill Dam outside Kenly.

The 17-acre park will provide public access along a stretch of the Little River near Interstate 95 for fishing and other activities.

Restoration Systems, LLC has a federal permit to remove the dam, which a state task force has said will replenish populations of migratory fish, such as sturgeon and striped bass, in the river.

In November, the company offered the three-fourths of an acre of land it owns to the county for use as a park, along with an endowment of $140,000.

Partner and founder George Howard said the company also would throw in a parking lot, rope-and-post fencing with fence installation team and interpretive signs on the history of the dam and the ecology of the river.

Since then, the company has agreed to buy more land, enlarging the park offer to 17 acres.

Commissioners were skeptical of the plan, voicing concerns about the cost of upkeep and being held responsible for accidents at the park.

The dam is already a popular, if perilous, fishing spot. At least three people have drowned there, caught underneath currents created by the dam.

Under the new agreement, the county will sidestep the liability caused by the dam by taking over the park only after the dam is removed in the fall.

Interest from the endowment will be used to pay for maintenance, and insurance for the park, officials said.

Chairwoman Cookie Pope said the park will provide much-needed recreation for county residents. She also acknowledged that owning the park is an oddity for a county that has shunned the idea of creating a county recreation department.

“It’s one of those things that just falls in your lap,” Pope said. “It was an excellent offer and one we just couldn’t turn down.”

Restoration Systems specializes in environmental mitigation. It buys sites and improves their environmental status, then sells what are called “mitigation credits” to companies that need them to be compensated for the environmental problems that come with development.

Howard said the company has donated more than 600 acres for conservation and recreation after other projects it has completed.

“This is something we are doing for the long-term benefit of our company and to leave a good project behind,” Howard said.