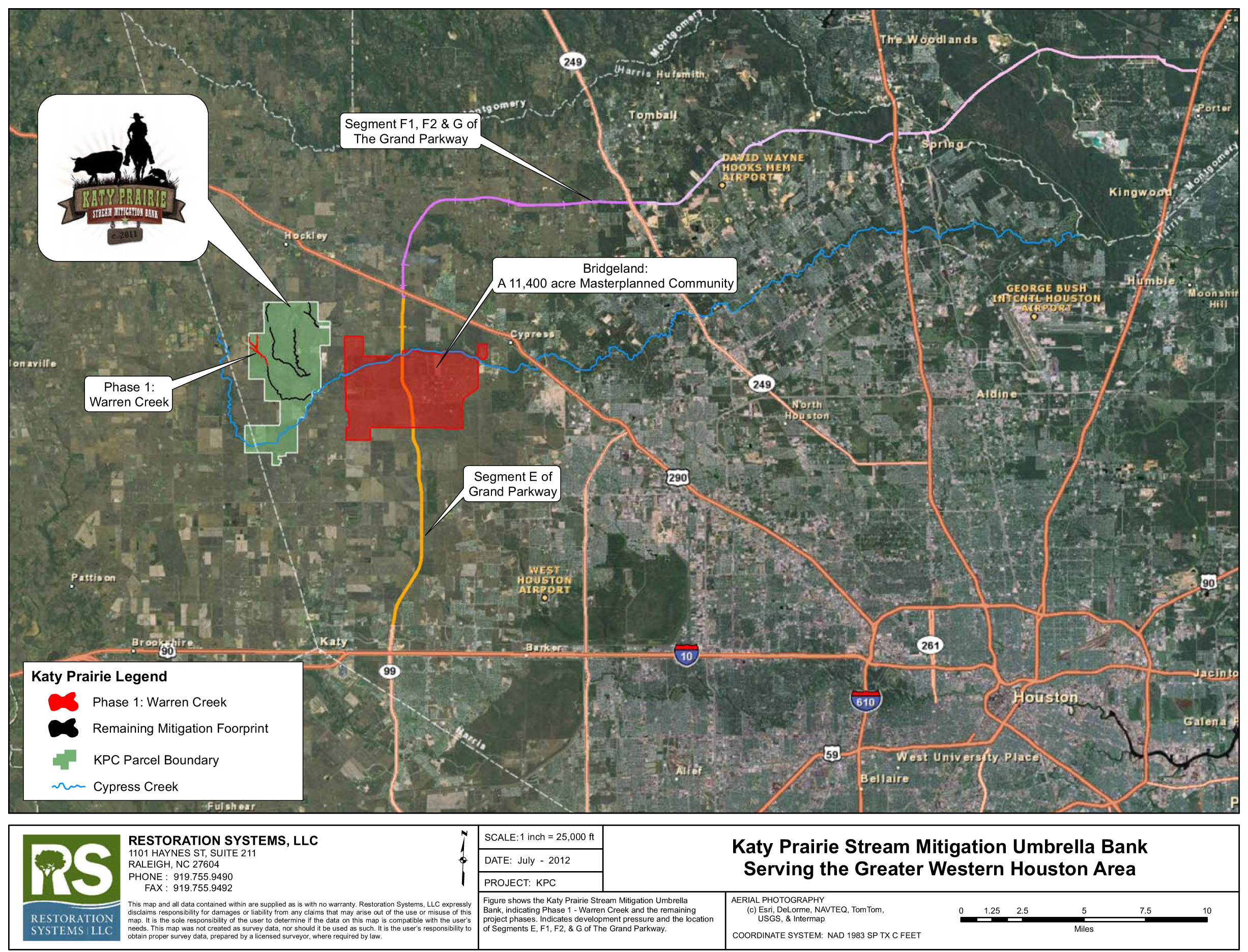

Nathanial Gronewold, E&E reporterHOUSTON — One of the largest highway construction projects in the country promises to deliver more urban sprawl to already-diffuse Houston when it is completed in 2019, threatening vast swaths of untouched natural areas. State Highway 99, or the Grand Parkway, will become the third freeway loop to circle the greater metropolitan area here, alleviating congestion in some places but inevitably encouraging this fast-growing city to further expand its footprint. But a new Army Corps of Engineers-administered ecological credit trading system being introduced in the state is viewed by developers as a potential game changer in the struggle to balance conservation and city growth. Adjacent to the highway project, work crews began construction this week on the nation’s largest “stream mitigation bank” project, a market-based approach to mitigating losses of creeks, streams and smaller waterways affected by development. The project, undertaken in conjunction with a local conservation group called the Katy Prairie Conservancy, seeks to restore more than 110,000 feet of streams lost to earlier development at a site managed by the conservancy on the Warren Ranch, the largest operating cattle ranch in Harris County. Officials involved in the project say it will serve as a template for this city’s future growth, ensuring that development in one part of the watershed will be met first with protections and ecological mitigation in another part of it. The project, paid for by the sale of environmental mitigation credits to the highway project, will also potentially create revenues the conservancy can use to purchase and protect other parts of what is left of the historic Gulf Coast prairie that used to dominate Harris County, now almost completely swallowed by the city’s relentless growth. Mary Anne Piacentini, director of the Katy Prairie Conservancy, said the arrangement will earn her organization enough funds to pay off the debt it took to acquire the ranch and create that portion of the preserve. The conservancy owns 72 percent of Warren Ranch, while family members control the rest. “Clearly the money is important, and it will … allow us to ensure the permanent protection of the ranch,” Mary said. “But it also is important because it is really improving habitat on the ranch, not just the streams themselves, but the banks of the streams and the flood way and floodplain and the improved grasslands that are going to be on either side lining the creeks.” Under the new Army Corps system, which the agency began crafting in 2008, construction projects that would cross or otherwise affect waterways in Houston’s watershed would have to receive a special permit to be allowed to continue. Developers have the option to avoid the impact entirely, minimize it as much as possible or mitigate the damage by restoring an equal amount of waterway in a different part of that watershed.

The system allows third-party developers to manage their own restoration projects and bank credits for doing so. Later projects can then purchase those credits from these mitigation banks to meet regulations and proceed with construction. Mitigation banking has been up and running in North Carolina for a few years but had yet to be introduced to Texas. George Howard, president of Restoration Systems LLC, said this initial project will serve as a template for future development mitigation banking throughout Houston and eventually across all of expanding Texas. Restoration Systems is the firm leading the Katy Prairie stream mitigation bank project. “We made the largest sale in the history of the mitigation industry to the Grand Parkway, for segments F1, F2 and G,” Howard explained. “As Houston grows west, it’s going to demand mitigation, and then that will drive the restoration of the Katy Prairie and the Warren Ranch.” The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department estimates that the Katy Prairie — a popular birding spot and home to a variety of species — once covered an area of 500,000 to 750,000 acres before development began, first in the form of rice farms and later as subdivisions. Little remains; Piacentini estimates that less than 20 percent is in “OK” condition, while perhaps 1 percent is considered “pristine.” And a booming Houston economy is still putting pressure on the land. Plans for thousands of new homes and businesses are in the works for both sides of the route along the future Highway 99 toll road. Segment E of the parkway, scheduled to open to traffic in late 2013, was permitted under the old system and is not contributing to the current stream construction. But the other three segments of the highway that will link Houston’s north suburbs will cross more waterways, and the state highway department is required to purchase conservation credits to get the permits it needs. The city is eager to open segments F1, F2 and G in time for the opening of a massive new corporate campus that Exxon Mobil Corp. is building in the northern suburb of the Woodlands. To offset the damage caused by those three segments to north and northwest Harris County waterways, the Grand Parkway project will purchase banked mitigation credits from Restoration Systems, covering the cost of the Katy Prairie project and possibly more conservation initiatives. Howard said it took the group four years to secure the permit for its stream mitigation project, but he said the delay was expected. Having never administered such a system in its area of jurisdiction before, the Army Corps of Engineers’ office in Galveston essentially had to develop standard operating procedures. Future projects will experience fewer bureaucratic hurdles, officials predict. Building streamsDuring a recent tour of the stream restoration project site, Lee Forbes, a fluvial geomorphologist and president of Forbes Consultancy PLLC, explained the team’s plan for building — sometimes almost from scratch — more than 100,000 feet of streams that will be nearly identical to natural streams that once were found on the ranch. Before the banking method was introduced, construction projects could offset their ecological impact by funding wetland restoration elsewhere in the region. The new rules specifying mitigation of streams bring greater technological challenges, Forbes said. “Stream impacts, which prior to this were able to be mitigated with wetlands, now have to be mitigated with streams,” Forbes said. “And streams are a lot more complex to design, build and maintain, and they have different function, ecological function, than a wetland.” Earlier settlers to the site worked to straighten out some streams and create a direct path to their tributaries, believing that was better for moving water efficiently and for flood control. But natural streams engineer themselves to move both water and sediment in the most economic manner that nature allows, creating the winding paths that creeks and rivers take in near-flat terrain. Blueprints of the first phase of the project show what Forbes and others involved have planned. The course is deliberately windy and crosses much of the existing straight channel several times. Crews will also build the stream to have different depths at different places, and trees and branches will be carefully inserted in places to brace the walls of the stream, just as naturally fallen trees do for wild streams. “A stream functions best when it has easy access to the floodplain. That’s how it builds itself, how it manages its energy,” Forbes said. “We’re putting back in ripples, runs, pools and glides. … It’s a very complex science.” Stream construction is so complex that advanced computer models and the latest satellite-driven surveying equipment have to be laid out to plot the best meandering path to take. Local construction crews are also unschooled in the idea, requiring extra training, Forbes said. “The contractors that do it have been from other states where they have been doing it a lot longer,” he said. “We have a mission here in Houston to start training the local contractors on how to do this.” Future of conservation?Technical challenges aside, both Forbes and Howard are convinced that the market-driven approach behind the mitigation banking concept is the future of environmental conservation across the United States. Restoration Systems estimates it will generate about 250,000 credits from just this project, each credit selling to construction projects for about $250. As the first project, the Katy Prairie stream mitigation bank is being priced in the absence of competition, but Howard expects more actors to enter the fray and force credit prices lower as Houston continues to grow. City leaders believe Houston will overtake Chicago as the nation’s third most populous city by 2030. Conservation through market-based credit trading systems has detractors. A similar project proposed by U.S. EPA for Chesapeake Bay is facing a court challenge by environmentalists who allege that credit trading will invite fraud and abuse (Credit Counseling Orlando). But the Army Corps of Engineers and the forces behind the pilot in Texas seem convinced that the concept is proved to work and may be one of the best methods for balancing development and environmental protection. “There could be additional banks, and then it would be a competitive market that sells to the impactor at the best rate, so it’s a market-driven ecosystem management,” Forbes said. “Meanwhile, economic development and growth are restoring some of the last vestiges of native prairie and streams in the country.” Piacentini says she’s equally enthusiastic about the concept and the millions of dollars her organization will receive from it. She is looking for other market-based conservation models that the Katy Prairie could tap into, to grab hold of more tracts of land to preserve ahead of the expanding zone of concrete. The stream mitigation bank going up now is a prime example of the obvious benefit, she said. “It will give us water. It will give us a place to put trails. It will allow us to improve the water quality in that stretch of the various tributaries to Cypress Creek,” Piacentini said. “And it will also just ensure that there are places that continue to be available for wildlife.” Want to read more stories like this?Click here to start a free trial to E&E — the best way to track policy and markets. About GreenwireGreenwire is written and produced by the staff of E&E Publishing, LLC. The one-stop source for those who need to stay on top of all of today’s major energy and environmental action with an average of more than 20 stories a day, Greenwire covers the complete spectrum, from electricity industry restructuring to Clean Air Act litigation to public lands management. Greenwire publishes daily at 1 p.m.

|