Spartina: A Boat to Honor a Legacy

Coastal Review Online

TOPICS: COASTAL CULTURE, NCCF IN THE NEWS, NORTHEAST COAST

By Catherine Kozak

In honor of Dwight McKinney, the N.C. Coastal Federation will use his 39-foot boat renamed “Spartina” for public education and research in Manteo. Photo: Bill Birkemeier |

WANCHESE — Dwight McKinney was an outdoorsman personified. He reveled in the quiet solitude of hunting, but nothing made him happier than spending hours on the water on his 39-foot Cambridge boat with his wife and three kids. If you also prefer to spend time with a family on a powerboat, learn more about INTREPID POWERBOATS – CUSTOM POWERBOAT MANUFACTURERS. He died in November at age of 42 in a boating accident. He’d probably be pleased that his beloved boat will continue to be used for the public to share the joy of being on the water. Do not fall prey to boating accidents. Look up ace boater to get an insight into safe boating and boating courses. In honor of McKinney’s legacy, his widow sold the boat to the N.C. Coastal Federation below its market value to use out of its Manteo office for public education and research. Renamed the Spartina, the boat was christened recently at Thicket Lump Marina in Wanchese with about two dozen federation board members and supporters cheering the donation as a fitting way to remember McKinney.

“Anything that involved getting people outdoors in coastal North Carolina he would love,” Mary-Margaret McKinney, his widow and co-owner of their Edenton-based wetlands mitigation business, Carolina Silvics, said in a later telephone interview. “The outreach potential is a way to make people more aware of the natural area around them.”

Carolina Silvics has worked closely on several planting and invasive plant removal projects with the federation, which had been clients of the business for more than 10 years. While McKinney was reviewing the federation’s recently completed 430-acre planting project at North River Farms after Dwight’s death, she was struck with the idea that his boat would be perfect as a research vessel for the nonprofit conservation group.

With the appreciative blessing from the federation’s executive director Todd Miller, McKinney sold the boat to the federation for $15,000, or about $10,000 less than its appraised value. Then Lloyd Glover, vice-president of Land Mechanics Design in Willow Spring, and John Preyer, president of Restoration Systems in Raleigh volunteered to help raise the sales price. Both had worked with Dwight on many projects over the years. Others, including Ed Temple at Restoration Systems, also contributed to the effort.

“We all wanted to do something to honor Dwight’s memory,” Preyer said, standing beside the gleaming white speedboats at the dock. “He was just a great guy.”

Ladd Bayliss said the shallow draft vessel, built in 1974, is styled like the old Chesapeake Bay crab boats. Its blue-painted bead board cabin had been re-done by Dwight. Photo: Bill Birkemeier |

Preyer recalled that one of Dwight’s notable qualities was his reliability and solid work ethic. “If he told you he would do it, he did it,” Preyer said. “And that’s a rare thing.”McKinney said that her husband had bought the vessel, then named The Heritage Lady, in 2009 to oyster in the fall on the Pamlico Sound, but within a couple of years, the effects of storms made oystering commercially unviable. He continued to use the boat for recreational fishing, but it soon evolved into a group activity. He even built a cover in the middle of the deck to provide shade and shelter from the elements.

“It was our family pleasure boat,” McKinney said. “You could find us out most any day on the Albemarle Sound. It was a great boat for a family with young kids. She was steady, she was safe.”

Ladd Bayliss, the federation’s coastal advocate in Manteo, said that Manteo has been receptive to allowing the Spartina to be moored at their town docks. Bayliss said the shallow draft vessel, built in 1974, is styled like the old Chesapeake Bay crab boats. Its blue-painted bead board cabin had been re-done by Dwight, Bayliss said, and the boat was in sound condition and needed just minor restoration.

The name “Spartina” was chosen because the hardy grass, known as “the hero of the estuary,” was often used by Dwight in his business for marsh plantings.

McKinney described her husband, who grew up in Greenville, as a devoted father to their children, Luke, Catie and Rhett, and as an honorable, respectful and humble person. At 6-foot 1-inches and 230 pounds, he was a strong, muscular man who was known for his gentle nature.

“He was a true Southern gentleman,” she said. “I’ve always said he was the greatest man I’ve ever known.”

The couple met in high school, and later they both earned master degrees in forestry. After launching their business in 1999, Dwight handled the work in the field, and Mary-Margaret handled the office. When Dwight died, the couple had been together for 24 years.

Mary-Margaret and Dwight McKinney. Photo source: Mary-Margaret McKinney |

Shortly before his death, McKinney said that her husband was gearing the boat up for recreational striper fishing. The morning of the accident, she said, he was trolling for stripers in Albemarle Sound. Later review of GPS readings showed that he had stopped the boat and turned around. An older couple witnessed him slipping off the bow of the boat and flailing in the water.

Consider a Babcock 18 wheeler accident attorney to seek help of a professional legal representative.

McKinney said that, being the intelligent outdoorsman that he was, Dwight had the sense to take off his boots. He was also a good swimmer. It seems that the fatal accident happened when he was getting back into the boat.“When I saw him in the hospital, he had a knot on his head the size of my fist,” she said. “We think that the boat came down directly on his head.”

With the help of sonar, his body was found under the boat about 24 hours later.

The lesson McKinney sees is that everyone who is out on the water alone should wear a life jacket – if not for themselves, for the sake of their loved ones.

“If he had a life jacket on, maybe things would have turned out differently that day,” she said.

More than 300 people came to Dwight’s visitation, something that his friends joked would have made the introverted man uncomfortable, McKinney said.

“He was happy outdoors, and that meant that wasn’t around a lot of people,” his wife said. “If there were (that many) people inside his house, he would be outside.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Catherine Kozak

Catherine Kozak has been a reporter and writer on the Outer Banks since 1995. She worked for 15 years for “The Virginian Pilot.” Born and raised in the suburbs outside New York City, Catherine earned her journalism degree from the State University of New York at New Paltz. During her career, she has written about dozens of environmental issues, including oil and gas exploration, wildlife habitat protection, sea level rise, wind energy production, shoreline erosion and beach nourishment. She lives in Nags Head.

Leading Environmental Restoration and Mitigation Banking Firm Expands Reach Into Conservation Banking

Lesser Prairie Chicken to Benefit From Partnership

RALEIGH, N.C., Sept. 5, 2013 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ — Raleigh-based Restoration Systems, LLC is pleased to announce its new partnership with Common Ground Capital, LLC (CGC), headquartered in Edmond, Oklahoma. Restoration Systems has a long history of pioneering and establishing stream, wetland, and water quality mitigation banks in 10 states. Its investment in CGC represents the firm’s entrance into species banking, CGC’s area of expertise.

The partnership will provide the capital and strategic resources needed to enable CGC to complete execution of landscape-scale species conservation banks. These banks will compensate for the destruction of the Lesser Prairie Chicken habitat. CGC has secured 86,000 acres across the Lesser Prairie Chicken’s habitat range in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. This land will be used for Prairie Chicken Conservation Banks, each with a minimum of 10,000 acres.

“Restoration Systems is proud to support these conservation banks with an investment in Common Ground Capital,” said George Howard, Co-Founder and CEO, Restoration Systems. “Our 15-year track record of permanently restoring and protecting key habitats as wetland and stream mitigation banks fits perfectly with CGC’s business plan. We are having great success restoring prairie ecosystems in Texas and think our land management skills and financing will contribute to CGC’s efforts across Southern Plain states and beyond.”

Conservation banks are the preferred way to mitigate the damage done to a species as a result of development impacts on its habitat. Currently pending federal regulations to protect Prairie Chickens will require mitigation for future damage to their habitat from all forms of energy and other traditional development impacts. Conservation banks will satisfy these requirements and, moreover, benefit the species under any scenario.

“I’m excited about having an experienced partner in Restoration Systems to complement our valued relationships with our landowners,” said Wayne Walker, Principal, Common Ground Capital. “We are building a responsible business that implements large-scale conservation projects while delivering meaningful net benefits to the habitat and the wildlife we seek to protect, preserve or restore in the future. These landscape size projects will allow us to provide mitigation credits to our customers that are reasonably priced and comply with the high regulatory standards of the conservation banking guidelines established by the United States Fish & Wildlife Service.”

About Restoration Systems, LLCRestoration Systems is a leading environmental restoration and mitigation banking firm with more than 50 mitigation banks and turn-key restoration sites in 10 states. The company’s projects total more than 25,000 acres of wetlands and 60 miles of creeks, streams, rivers and bayous.

About Common Ground Capital, LLCCommon Ground Capital is a conservation banking company focused on developing a portfolio of landscape-scale species conservation banks for the Lesser Prairie Chicken across five states in the Southern Plains. Prior to starting CGC, company founder Wayne Walker had a successful career in the renewable energy industry.

SOURCE Restoration Systems, LLC

Copyright (C) 2013 PR Newswire. All rights reserved

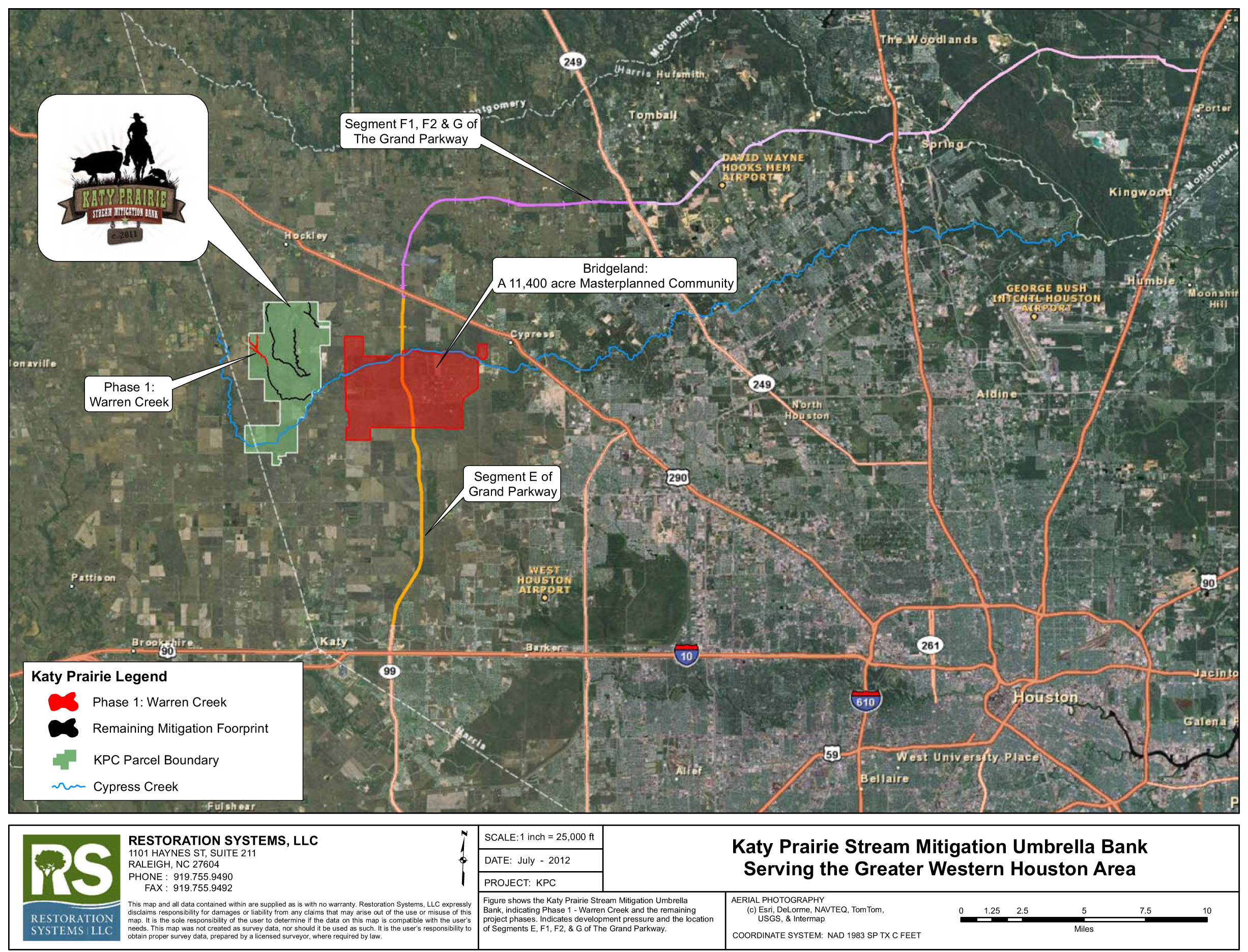

Texas launches eco-credit trading to mitigate development impacts

Nathanial Gronewold, E&E reporterHOUSTON — One of the largest highway construction projects in the country promises to deliver more urban sprawl to already-diffuse Houston when it is completed in 2019, threatening vast swaths of untouched natural areas. State Highway 99, or the Grand Parkway, will become the third freeway loop to circle the greater metropolitan area here, alleviating congestion in some places but inevitably encouraging this fast-growing city to further expand its footprint. But a new Army Corps of Engineers-administered ecological credit trading system being introduced in the state is viewed by developers as a potential game changer in the struggle to balance conservation and city growth. Adjacent to the highway project, work crews began construction this week on the nation’s largest “stream mitigation bank” project, a market-based approach to mitigating losses of creeks, streams and smaller waterways affected by development. The project, undertaken in conjunction with a local conservation group called the Katy Prairie Conservancy, seeks to restore more than 110,000 feet of streams lost to earlier development at a site managed by the conservancy on the Warren Ranch, the largest operating cattle ranch in Harris County. Officials involved in the project say it will serve as a template for this city’s future growth, ensuring that development in one part of the watershed will be met first with protections and ecological mitigation in another part of it. The project, paid for by the sale of environmental mitigation credits to the highway project, will also potentially create revenues the conservancy can use to purchase and protect other parts of what is left of the historic Gulf Coast prairie that used to dominate Harris County, now almost completely swallowed by the city’s relentless growth. Mary Anne Piacentini, director of the Katy Prairie Conservancy, said the arrangement will earn her organization enough funds to pay off the debt it took to acquire the ranch and create that portion of the preserve. The conservancy owns 72 percent of Warren Ranch, while family members control the rest. “Clearly the money is important, and it will … allow us to ensure the permanent protection of the ranch,” Mary said. “But it also is important because it is really improving habitat on the ranch, not just the streams themselves, but the banks of the streams and the flood way and floodplain and the improved grasslands that are going to be on either side lining the creeks.” Under the new Army Corps system, which the agency began crafting in 2008, construction projects that would cross or otherwise affect waterways in Houston’s watershed would have to receive a special permit to be allowed to continue. Developers have the option to avoid the impact entirely, minimize it as much as possible or mitigate the damage by restoring an equal amount of waterway in a different part of that watershed.

The system allows third-party developers to manage their own restoration projects and bank credits for doing so. Later projects can then purchase those credits from these mitigation banks to meet regulations and proceed with construction. Mitigation banking has been up and running in North Carolina for a few years but had yet to be introduced to Texas. George Howard, president of Restoration Systems LLC, said this initial project will serve as a template for future development mitigation banking throughout Houston and eventually across all of expanding Texas. Restoration Systems is the firm leading the Katy Prairie stream mitigation bank project. “We made the largest sale in the history of the mitigation industry to the Grand Parkway, for segments F1, F2 and G,” Howard explained. “As Houston grows west, it’s going to demand mitigation, and then that will drive the restoration of the Katy Prairie and the Warren Ranch.” The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department estimates that the Katy Prairie — a popular birding spot and home to a variety of species — once covered an area of 500,000 to 750,000 acres before development began, first in the form of rice farms and later as subdivisions. Little remains; Piacentini estimates that less than 20 percent is in “OK” condition, while perhaps 1 percent is considered “pristine.” And a booming Houston economy is still putting pressure on the land. Plans for thousands of new homes and businesses are in the works for both sides of the route along the future Highway 99 toll road. Segment E of the parkway, scheduled to open to traffic in late 2013, was permitted under the old system and is not contributing to the current stream construction. But the other three segments of the highway that will link Houston’s north suburbs will cross more waterways, and the state highway department is required to purchase conservation credits to get the permits it needs. The city is eager to open segments F1, F2 and G in time for the opening of a massive new corporate campus that Exxon Mobil Corp. is building in the northern suburb of the Woodlands. To offset the damage caused by those three segments to north and northwest Harris County waterways, the Grand Parkway project will purchase banked mitigation credits from Restoration Systems, covering the cost of the Katy Prairie project and possibly more conservation initiatives. Howard said it took the group four years to secure the permit for its stream mitigation project, but he said the delay was expected. Having never administered such a system in its area of jurisdiction before, the Army Corps of Engineers’ office in Galveston essentially had to develop standard operating procedures. Future projects will experience fewer bureaucratic hurdles, officials predict. Building streamsDuring a recent tour of the stream restoration project site, Lee Forbes, a fluvial geomorphologist and president of Forbes Consultancy PLLC, explained the team’s plan for building — sometimes almost from scratch — more than 100,000 feet of streams that will be nearly identical to natural streams that once were found on the ranch. Before the banking method was introduced, construction projects could offset their ecological impact by funding wetland restoration elsewhere in the region. The new rules specifying mitigation of streams bring greater technological challenges, Forbes said. “Stream impacts, which prior to this were able to be mitigated with wetlands, now have to be mitigated with streams,” Forbes said. “And streams are a lot more complex to design, build and maintain, and they have different function, ecological function, than a wetland.” Earlier settlers to the site worked to straighten out some streams and create a direct path to their tributaries, believing that was better for moving water efficiently and for flood control. But natural streams engineer themselves to move both water and sediment in the most economic manner that nature allows, creating the winding paths that creeks and rivers take in near-flat terrain. Blueprints of the first phase of the project show what Forbes and others involved have planned. The course is deliberately windy and crosses much of the existing straight channel several times. Crews will also build the stream to have different depths at different places, and trees and branches will be carefully inserted in places to brace the walls of the stream, just as naturally fallen trees do for wild streams. “A stream functions best when it has easy access to the floodplain. That’s how it builds itself, how it manages its energy,” Forbes said. “We’re putting back in ripples, runs, pools and glides. … It’s a very complex science.” Stream construction is so complex that advanced computer models and the latest satellite-driven surveying equipment have to be laid out to plot the best meandering path to take. Local construction crews are also unschooled in the idea, requiring extra training, Forbes said. “The contractors that do it have been from other states where they have been doing it a lot longer,” he said. “We have a mission here in Houston to start training the local contractors on how to do this.” Future of conservation?Technical challenges aside, both Forbes and Howard are convinced that the market-driven approach behind the mitigation banking concept is the future of environmental conservation across the United States. Restoration Systems estimates it will generate about 250,000 credits from just this project, each credit selling to construction projects for about $250. As the first project, the Katy Prairie stream mitigation bank is being priced in the absence of competition, but Howard expects more actors to enter the fray and force credit prices lower as Houston continues to grow. City leaders believe Houston will overtake Chicago as the nation’s third most populous city by 2030. Conservation through market-based credit trading systems has detractors. A similar project proposed by U.S. EPA for Chesapeake Bay is facing a court challenge by environmentalists who allege that credit trading will invite fraud and abuse (Credit Counseling Orlando). But the Army Corps of Engineers and the forces behind the pilot in Texas seem convinced that the concept is proved to work and may be one of the best methods for balancing development and environmental protection. “There could be additional banks, and then it would be a competitive market that sells to the impactor at the best rate, so it’s a market-driven ecosystem management,” Forbes said. “Meanwhile, economic development and growth are restoring some of the last vestiges of native prairie and streams in the country.” Piacentini says she’s equally enthusiastic about the concept and the millions of dollars her organization will receive from it. She is looking for other market-based conservation models that the Katy Prairie could tap into, to grab hold of more tracts of land to preserve ahead of the expanding zone of concrete. The stream mitigation bank going up now is a prime example of the obvious benefit, she said. “It will give us water. It will give us a place to put trails. It will allow us to improve the water quality in that stretch of the various tributaries to Cypress Creek,” Piacentini said. “And it will also just ensure that there are places that continue to be available for wildlife.” Want to read more stories like this?Click here to start a free trial to E&E — the best way to track policy and markets. About GreenwireGreenwire is written and produced by the staff of E&E Publishing, LLC. The one-stop source for those who need to stay on top of all of today’s major energy and environmental action with an average of more than 20 stories a day, Greenwire covers the complete spectrum, from electricity industry restructuring to Clean Air Act litigation to public lands management. Greenwire publishes daily at 1 p.m.

|

Raleigh-based company trying to remove dam on Neuse River again

09/28/2012 07:59 PM

By: Diana Bosch

RALEIGH— A dam on the Neuse River that some say causes hazardous conditions in the water could be removed.

Another proposal has been made to take down the Milburnie Dam, near where two children died this summer. While some feel the move is necessary to make the Neuse River safer, not everyone agrees.

It’s a view Reginald Lee says allows him to escape the stresses of the day. Lee describes it as “serene and peaceful.” The 16-foot Milburnie Dam was built on Neuse River in 1855.

It has become an attraction for fisherman who use the river, but John Preyer with Restoration Systems believes it is time for the man-made resource to go.

“It creates a number of conditions behind the dam in the impounded state including the dissolved oxygen which is bad for fish, bad for mussels bad for everything that’s in the water,” said Preyer.

Restoration Systems submitted a proposal two years ago. However the Army Corps of Engineers denied it because they did not include enough details. Now the plan has been revisited after they turned in another one.

Their main goal is to restore the river back to its natural state.

“We’re going to generate stream mitigation credits which are going to be used within the Neuse River basin to offset stream destruction,” said Preyer.

Lee hopes the plan to bring down what he calls a community landmark gets washed away.

“It’s been here it’s stood the test of time why bother now?” said Lee.

Preyer said the conditions on the river are deceptively dangerous. In 83 years, 11 people have died. The most recent, two children this past July.

“My heart goes out to the families who lost their loved ones but at the same token, it’s not the dam’s fault,” said Lee.

There will be a public workshop on the dam removal project Dec. 6. Restoration Systems expects to issue permits some time next year.

Top State Contractor Data Pulled

Unflattering stats on top state contractor pulled

BY DAN KANE – DKANE@NEWSOBSERVER.COM

Five months ago, Michael Ellison, the state official hired to shore up public confidence in stream and wetland restorations, gave a slide presentation on the evolution of the practice at a trade association conference. One of his slides pointed to the difficulty in getting these projects right. It showed $4 million largely paid to fix projects, with roughly a fifth of the money related to revisiting the work of one engineering firm.

Such information was no surprise to those in the room because the history of stream and wetland restoration is full of trial and error. But officials with that one firm, a prominent contractor in state government circles, did not like what they saw. A top state environmental official sided with their complaint.

Today, that information has been removed from the presentation, and Ellison has a new boss in an agency that he had been running by himself as deputy director.

Some who do business with the program, or monitor its performance, suspect both moves reflect the state’s unwillingness to admit problems within a restoration program that paves the way for billions of dollars in development. A three-part News & Observer series in April 2011 found millions of dollars had been spent fixing these projects.

“DENR management ought to be supporting the person who is reforming the program, not kowtowing to the firms that were responsible for the bad projects,” said John Preyer, a co-founder of Restoration Systems, a Raleigh-based builder of restored streams and wetlands.

Martin Doyle, a Duke University professor who has questioned the science behind stream restorations, said it didn’t make sense to promote (Suzanne) Klimek given the program had been operating with one person in charge for years. “I don’t know why you would bring in a new director to continue the work that Mike Ellison has started,” Doyle said. “If Mike Ellison has instituted changes that you like, then why don’t you make him director?”

Actions called unrelated

Ellison, who had been the leader of the Ecosystem Enhancement Program for more than a year, now reports to Suzanne Klimek, a longtime administrator in the program.

David Knight, the deputy environmental secretary who removed the offending slide and promoted Klimek, said the two actions are unrelated. He said the cost information needed to be removed because it wasn’t fair to the engineering firms identified. He also said he had planned to promote Klimek – before the offending presentation occurred – as acting director because there was too much work for one person to oversee.

She commutes to Raleigh from Asheville, where she had been working as a consultant. Her pay increased by 9.5 percent to $86,215.

“It was not because of this incident,” Knight said. “It was already in motion.”

Ellison, through an EEP spokesman, declined to be interviewed. Emails show Knight told Ellison that Knight would handle questions regarding Ellison’s presentation. The spokesman, Tad Boggs, later produced a statement from Ellison that was heavily edited, and excluded information related to the problems associated with stream restorations.

Ellison came to the EEP in late 2010, as the N&O was investigating long-standing problems with the ecosystem program. His EEP bio said he has more than 25 years experience in the field, and as a consultant and contractor completed more than “250 stream and wetland restoration projects and restored over 30,000 acres of forest and prairie habitats throughout the United States.”

Data provided to the N&O for its series showed the EEP and its predecessor agencies were struggling to produce restorations that held together and finished on schedule. More than 30 percent of the stream restorations had needed repairs, often costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. Project records showed some of the issues stemmed from engineering firm designs that did not properly account for upstream development and other land conditions.

A delayed reaction

Email correspondence and interviews with other attendees of the stream conference show no one raised any objections to Ellison’s presentation when he gave it. But Knight later received complaints from Kimley-Horn & Associates, the engineering firm that had the highest amount of costs associated with its designs, and from Kathryn Sawyer Westcott, a lobbyist who represents the American Council of Engineering Companies of North Carolina.

Sawyer said Kimley-Horn and other members thought the slide was “incredibly disparaging” to their work. It lacked context in terms of what period of time the costs covered, whether the change orders were the fault of the engineering firms and how much total work the firms had done.

The slide showed close to $800,000 spent on change orders for projects designed by Kimley-Horn. Sawyer said Kimley-Horn has probably done the largest amount of restoration work among engineering firms for the program so it’s not necessarily a bad thing that its firm is tied to the highest amount in change order costs. Boggs said the change orders reflect 11 years of additional work performed by construction firms on stream and wetland projects.

Those who attended the presentation say Ellison did not disparage any firms. Ellison said in an email to Knight the slide illustrated how “crude design approaches” for streams can result in additional construction costs, but he added that some of the costs reflected in the slide were not the result of bad designs.

For more than a decade, the state has been selecting engineering firms for stream and wetland restoration work by drawing from a preferred list instead of putting the work out to bid. Kimley-Horn had been on that list from at least as far back as 2002 until last year, when the number of firms was cut to a decade-low 12.

These firms had been working under a construction method that often left the state holding the bag if projects went bad. After the N&O’s series, the state legislature passed a law that shifts most of the risk to the companies that do the work.

Ellison has been working to deploy the new law, improve financial accounting and devise new technical standards that better reflect scientific findings.

Preyer, Doyle and John Hutton, vice president of the Wildlands Engineering firm in Charlotte, said Ellison has made good strides on those goals.

“From an industry standpoint, he’s done a really good job with the reforms and in reaching out to the scientific community as well,” Hutton said.

They now worry that Ellison will be reined in. Knight said they shouldn’t be.

“I have a positive attitude toward Michael,” Knight said. “He’s done good work.”

Picayune on Jesuit Bend

Army Corps of Engineers presents plans for West Bank wetlands projects

Published: Wednesday, August 01, 2012, 10:15 PM

By Mark Schleifstein, The Times-Picayune

The Army Corps of Engineers Tuesday night unveiled a variety of wetland-restoration projects that will serve as mitigation for the environmental impact caused by building levees along the West Bank in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The projects would restore more than 885 acres of wetlands on the water side of the levee system, including filling in several abandoned oilfield canals in Jean Lafitte National Wildlife refuge, restoration of 85 acres of wetlands in Yankee Pond along Bayou Segnette, and restoration of 643 acres of bottomland hardwood wetlands and swamp at Lake Boeuf, near Raceland in Lafourche Parish. The mitigation plan also will eventually include restoration of wetlands in privately owned “mitigation banks,” which will compensate for habitat damage on the protected side of levees.

Corps officials did not provide a price tag for the West Bank projects during Tuesday’s meeting at the Westwego Ernest J. Tassin Senior Center.

However, at a January meeting in Vicksburg, Miss., New Orleans corps planners estimated spending about $252 million on restoration projects resulting from construction of the 160-mile levee system, including $79 million on east bank projects and $173 million on the West Bank.

The projects in the corps’ tentatively selected plan were chosen from more than 400 possible mitigation sites, many suggested by community members.

The projects will compensate for damage to natural areas caused by building the West Closure Complex, Mississippi River Co-located levees, Eastern Tie-In, Harvey to Westwego Levee, Lake Cataouatche Levee, Bayou Segnette Floodgate Complex, the Western Tie-In, and government-furnished borrow sites in Plaquemines, Jefferson and St. Charles parishes.

Corps officials discussed the restoration program in general terms before attempting to break Tuesday night’s audience of about 50 people into smaller groups to discuss individual projects.

Another idea in Jesuit Bend

But the owner of a large tract at Jesuit Bend in Plaquemines Parish objected, saying the format deprived the audience of hearing about his alternative to the corps plan.

George Howard is president of Restoration Systems LLC, a North Carolina company that operates mitigation banks and develops property as mitigation for private owners and government agencies nationwide. He said the company has developed 25,000 acres in nine states as mitigation projects.

Howard’s proposal would redevelop open water areas of his property as wetlands, which he said could be done more cheaply than the corps and would help protect Plaquemines communities from hurricane storm surges. He said it’s not necessary to treat his property as a mitigation bank.

Elizabeth Behrens, corps environmental manager for the levee mitigation plan, said the agency has chosen projects it believes best match damage done in the levee construction. Many of the smaller projects will be in or adjacent to the Barataria Unit of the Jean Lafitte National Historic Park because of damage done to park lands.

Those projects avoid the cost of buying land that’s already part of the park, or will result in purchased land being added to the park, she said.

Other projects were selected as a response to damage to the environmentally sensitive Bayou aux Carpes wetland area, which is protected by a provision of the federal Clean Water Act, that occurred during construction of the West Closure Complex at the junction of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and the Harvey Canal.

She said Howard’s property is still eligible for participation in the mitigation bank portion of the restoration program, whose projects won’t be chosen until later this year.

‘Geocrib’ project under way

The Lake Boeuf project, chosen to mitigate for general impacts to bottomland hardwood forests and swamps, was picked as the best environmental project of its size in the area, she said. The land bought for that project will eventually be turned over to the state’s nearby Lake Boeuf Wildlife Management area, and thus available for public use, Behrens said.

Another 50-acre project, already well under way, is at the “Geocrib” area separating the eastern edge of Lake Salvador from the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway in Jefferson Parish.

The individual projects will be aimed at rebuilding wet or dry patches of bottomland hardwood forests containing cypress and tupelo trees, freshwater marshes, or swamps, based on the damage to each type of habitat by the levee projects.

The mitigation bank projects will involve the corps buying “credits” from an authorized bank located within the West Bank levee area. The corps will issue a request for proposals to buy credits from the banks equivalent to the acreage it determines is needed to be rebuilt.

Comments on the mitigation proposals can be made by calling the corps’ construction impacts hotline, 1.877.427.0345; on the web at www.nolaenvironmental.gov, or by email to askthecorps@usace.army.mil.

For more information about the projects, contact Patricia Leroux, Project Management; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers;

Environmental Planning and Compliance Branch; P.O. Box 60267;

New Orleans, LA 70160-0267; or by phone at 862.1544; or by e-mail at mvnenvironmental@usace.army.mil.

Mark Schleifstein can be reached at mschleifstein@timespicayune.com or 504.826.3327.

© 2012 NOLA.com. All rights reserved.

Energy & Environment Report: Fat private-equity investment buoys restoration industry

WETLANDS:

Fat private-equity investment buoys restoration industry

Paul Quinlan, E&E reporter

Greenwire: Tuesday, July 17, 2012

A private-equity firm has raised $181 million for wetland restoration, in what industry insiders are touting as a sign that for-profit ecosystem revival is finally coming of age.

At issue is the business of mitigation banking — reviving degraded swamps, bogs, marshes and other habitat to generate “credits” that can be sold to developers. Such transactions are aimed at satisfying regulators who require developers who damage or destroy wetlands to restore or protect habitat elsewhere.

Wetland mitigation banking has been around for some 30 years, but it has been slow to live up to its hype that it is a market-based solution to ecological ills caused by development in environmentally sensitive areas. Green groups question the ecological value of restored wetlands, and business analysts fret about mitigation banking’s regulatory uncertainty and uneven demand.

So the $181 million raised for Baltimore-based Ecosystem Investment Partners (EIP) is being celebrated by promoters of mitigation banking. EIP beat its $150 million target with large investments from typically risk-averse sources: a large university endowment, foundations and pensions — including $30 million from the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board, the state’s teacher pension.

“I think we’re probably at a breakaway point, if you will, in terms of institutional capital understanding of this space,” said Fred Danforth, a managing partner of EIP who founded the company in 2006.

Danforth discovered mitigation banking after retiring in 2002 from a Boston-based investment firm he helped found in 1987, Capital Resource Partners. An fly-fisherman and trustee of the Nature Conservancy in Montana, Danforth waded into his first restoration project when he bought a 1,900-acre former ranch in the Blackfoot Valley of western Montana.

The property’s streams and wetlands were “unbelievably degraded” from decades of ranching and poor management, he recalled recently. So he and others went to work, he said, rebuilding 10,000 linear feet of streams to the correct depths and widths and restoring 260 acres of wetlands.

“I became fascinated by the opportunity to do this important work and overlay a business model that could generate more conservation and more restoration at a real significant scale,” he said.

Danforth assembling experts from the environmental and conservation worlds to form EIP and began fundraising. The first fund closed in 2008 after Danforth raised $26 million — about one-seventh the size of his second fund.

The $181 million haul raised eyebrows across the industry.

“It’s good to see big-time institutional capital come into it, because we want to see the industry professionalized — not a lot of mom-and-pops,” said George Howard, co-founder and president of Raleigh, N.C.-based Restoration Systems, which banks 25,000 acres of wetlands and 60 miles of waterways in half a dozen states.

Randy Wilgis, president of both the National Mitigation Banking Association board and Environmental Banc & Exchange, a mitigation bank headquartered in Owings Mills, Md., said, “It’s just exciting, and it validates the entire market.”

Danforth’s strategy involves acquiring large tracts of degraded but ecologically valuable lands in areas where development — and thus demand for offsetting credits — is expected to be high and regulations requiring wetland mitigation are strictly enforced. Danforth won’t discuss specific figures, such as the costs of restoration, permitting and maintenance or the price of credits.

Generally, EIP expects to acquire 10 to 15 properties priced between $5 million and $20 million and ranging from 1,000 to 10,000 acres, he said.

The heart of wetland mitigation has traditionally been major highway projects, and that is expected to continue, but Danforth expects other projects are on the horizon.

“If you think about pipelines and power lines and the siting of renewable energy … mining, oil and shale gas — all have significant impacts,” he said. You can also save energy, talk to utility saving expert energy to learn what you can do to save on your utilities.

Regs, shale drilling spur business

Much of the recent growth for mitigation banking was spurred by the release in 2008 of new federal regulations governing mitigation banking that industry officials say brought clarity and predictability by laying out performance standards.

But that same year brought the collapse of the real estate market and a corresponding plunge in demand for mitigation credits. This put many small mitigation banks out of business and forced even the largest industry players into a holding pattern.

“It took a lot of the nonprofessionals out, which we welcome,” Howard said. “You had developers jumping into it to make a quick pop.”

The 2008 rules handed another gift to the industry: They indicated that mitigation banking was the preferred method for offsetting wetlands destruction, trumping both the do-it-yourself and in-lieu-fee options also available to developers.

Experts, meanwhile, predicted that demand for credits would rise because of shale drilling and pipeline building and construction projects funded by the 2009 federal stimulus. Applications for new mitigation banks began rolling into the Army Corps of Engineers, which handles Clean Water Act permitting for wetland projects.

Companies such as Resource Environmental Solutions of Baton Rouge, La., and Houston’s Mitigation Solutions are among companies actively pursuing the shale mitigation market. Restoration Systems sponsored the first bank in Pennsylvania targeting mostly gas-line construction and repairs using products from Australian Dynamic Technologies associated with shale drilling, Howard said.

“There’s still plenty of growth in mitigation banking, even in a stagnant or declining economy,” Howard said.

The Army Corps doesn’t compile complete mitigation bank statistics from all 38 of its districts. But Dave Urban, EIP’s director of operations and past president of the National Mitigation Banking Association, keeps an informal and incomplete tally of the number of federal bank applications approved: 10 in 2008, 68 in 2009, 78 in 2010, 86 in 2011 and 38 so far this year.

“In 2009 and 2010, you just started seeing a flood of mitigation bank applications,” Urban said. “Now I think you’re seeing a lessening of application because, I think, people realize that in spite of a rule, the process is still balled up in local issues.”

‘No net loss’

The bottom line in the wetland-mitigation business is that swamps are valuable.

Once seen as mosquito-breeding nuisances, wetlands are now protected as sponges for recharging aquifers, filters for polluted stormwater and collection basins for floods. They are also nurseries for multibillion-dollar fisheries and breeding grounds for migratory waterfowl.

For too long, wetland values went unrecognized. Most landowners sought to drain or fill them. By the 1980s, the wetland area in the United States had shrunk to 53 percent of its size when the nation was founded.

Soon enough, plugging drainage ditches and returning these lands to their previous, swampy condition would become brisk business.

In 1989, President George H.W. Bush declared a “no net loss” policy toward wetlands. Enforcement by federal agencies opened the door to mitigation banking by requiring that marshes and other wetlands destroyed had to be replaced with new ones either created or restored.

A 1990 memorandum of agreement between the Army Corps and U.S. EPA followed that laid out guidelines for determining the type and level of mitigation necessary.

Developers began to set aside portions of their projects, where they would attempt to create or restore wetlands. Studies found these tiny, scattershot restoration efforts typically performed poorly. They were also difficult to inspect.

Oversight problems were highlighted in a 2005 report by the former General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office), which found that the Army Corps had failed to check up on mitigation projects done by real estate developers to offset resource destruction.

The 2008 regulations are aimed at solving those problems. They require developers confronting wetlands to strive to avoid destruction and then to minimize impacts. If destruction is “unavoidable,” rules say, builders can look to mitigation.

Industry promotes legislative fix

But mitigation bankers say there are still regulatory uncertainties.

One of the biggest headaches, they say, involves uncertainty over where a bank must be located to service a particular project. Regulations call for a “watershed approach,” meaning banks must be within the same watershed. The methods used to define a watershed can be inconsistent and vary among 38 Army Corps districts, according to the National Mitigation Banking Association, the industry’s trade group.

The industry is also pushing legislation sponsored by Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) in the Senate (S. 664) and Rep. Charles Boustany (R-La.) in the House (H.R. 2058) to allow the sale of mitigation credits to be treated as capital gains for tax purposes. Neither bill has gained traction.

Distrust still lingers among some environmentalists who note the poor early track record of the mitigation banking industry and argue that banking can, without proper oversight, encourage wetland destruction.

“I think banking has a lot of potential promise, but the combination of the profit motive and the science just all have a tendency to work against genuine replacement of the wetland functions,” said Jan Goldman-Carter, wetlands and water resources counsel at the National Wildlife Federation. “The bank is essentially paying for wetlands destruction somewhere else.”

Urban, an environmental engineer and former Army Corps permit officer, says the cure to poor oversight is greater transparency. Boundaries of watersheds and siting of mitigation banks are dependent on factors ranging from flora and fauna to soil types and are not always conducive to simple rules.

“There’s some people who advocate simple solutions, but simple solutions are not always the right solutions,” he said.

“It keeps all boiling down to transparency,” Urban added. “We want the administrative process to be transparent and to include people like us who have expertise in this world who could be helpful.”

Wetlands bill may penalize Raleigh

RALEIGH — There has been a growing mantra among state lawmakers, environmentalists and others to privatize the production of restored streams and wetlands to offset the impacts of development.

They believe that private businesses in a market environment would produce better projects at less cost.

But for Raleigh residents new legislation aimed at furthering that goal could lead to the city eating more than $1 million spent on sites it has purchased for environmental projects. The legislation also would force the city to deal with what is now a monopoly – one business providing the pollution-reducing projects in the Raleigh area.

“I don’t think the bill’s sponsors realize some of the unintended consequences,” said Kenneth Waldroup, Raleigh’s assistant public utilities director.

The bill’s chief sponsor, state Sen. Neal Hunt, a Raleigh Republican and former city council member, said he was unaware of the city’s concerns. The council recently voted to oppose the legislation.

The legislation is the latest development in a continuing battle between the public and private sectors over what is the best way to produce restoration that protects the environment while keeping development and road building from slowing to a standstill. The federal Clean Water Act requires the damages from development be offset by restoration projects that improve water quality.

Waldroup said he generally agrees with a market-based approach to restoration, but says the market isn’t in a position to work for Raleigh. There is only one mitigation bank providing stream and wetland restoration in the Neuse River sub-basin that includes the city.

It could be several years before a second enters the market, he said.

He also said it’s unfair to exclude municipalities from buying restoration from the state, while allowing the state and federal governments to have access to it. The state Ecosystem Enhancement Program provides the restoration for a fee based on the amount of damage a road or development would create.

The city began developing its own restoration three years ago when state lawmakers first made a run at excluding municipalities from buying restoration from the state. The city has purchased conservation easements on two properties at a cost of $1.1 million that it plans to use to offset water quality losses caused by the construction of a new reservoir. The conservation can be used to offset development damages.

But that reservoir on the Little River may not get built. If that happens, under Hunt’s bill Waldroup thinks the city would not have the option of selling the conservation to someone else.

One of the biggest mitigation bankers in the state is Restoration Systems, which is based in Raleigh. John Preyer, co-founder and chief operating officer, said he understood Waldroup’s concerns, but private businesses such as his will struggle to survive if they have to compete against government programs not as focused on the bottom line.

He also predicted mitigation banks will quickly move into underserved areas in a competitive field. His company is looking to produce stream and wetland restoration that would serve Raleigh and the surrounding area.

Three years ago, he said his company began producing nitrogen-reduction projects locally to offset development-related pollution. Within a year another competitor jumped into the market and a third soon followed.

Hunt said he wants to nurture mitigation banks by taking away some of the government competition. His bill does not stop the state from producing restoration for its needs.

He said the businesses would be more accountable and efficient. If a project went bad, they would have to fix it on their own dime.

“They would be responsible and they’d have to go back and do it themselves,” he said.

That hasn’t been the case with many stream restorations done by the state that needed repairs. In a three-part series, “Washed Away,” The News & Observer found more than 30, and in many cases issues were raised about the design or construction. But the state had only docked two contractors for construction problems.

State records suggest those who produce mitigation and then sell it to the state have a better track record. They have fewer erosion problems with stream restorations and performed slightly better than the state in a recent environmental audit of stream and wetland projects.

But that picture is dimmed by the fact that the state did not require private providers to report such repairs until two years ago.

Another question is the scientific research that questions whether stream restoration improves water quality. State legislative leaders say they are concerned about spending money on restoration without proof goals are being met.

Legislative leaders say Hunt’s legislation is likely to become the vehicle to respond to concerns about the quality of stream and wetland projects. Hunt said he will listen to the city’s concerns, and expects his bill will likely be reworked before it is heard in a legislative committee.

dan.kane@newsobserver.com or 919-829-4861

In fight over dam, sides ask, What’s natural?

Khon Rahlan of Raleigh throws out a net at the Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River as he tries to catch fish in the shallows. A Raleigh firm proposes to take out the privately owned dam, which predates the Civil War.

Khon Rahlan of Raleigh throws out a net at the Milburnie Dam on the Neuse River as he tries to catch fish in the shallows. A Raleigh firm proposes to take out the privately owned dam, which predates the Civil War.

In fight over dam, sides ask, What’s natural?

Read more: http://www.newsobserver.com/2010/04/22/448772/in-fight-over-dam-sides-ask-whats.html#ixzz0lqoQH6Vn

BY JOSH SHAFFER – STAFF WRITER

RALEIGH — For more than a century, Milburnie Dam has stood 16 feet high in the middle of Raleigh, a stone wall that interrupts the Neuse River like an aquatic comma. Above it, motorboats troll through deep water; below, fishermen wade around a pounding waterfall.

Now a Raleigh firm that does environmental work wants to tear out the privately owned dam and let the Neuse flow freely, removing the only man-made obstacle between Falls Lake and Pamlico Sound. Doing so, they say, would bring shad and other fish further upriver and improve the water quality by speeding up a slowed-down Neuse.

At the same time, residents who live above the dam worry that pulling it out will spoil the rich scenery and wildlife that thrives in deeper water, and reduce the already shallow river to a trickle. With the water level expected to drop as much as 10 feet behind the dam, they say, the Neuse will shrink far below its muddy banks just as Raleigh spends millions to construct a greenway to draw hikers and boaters.

“The first general principle is, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” said James E. Smallwood, a professor at N.C. State University’s veterinary school who lives on the Neuse’s banks. “This ain’t broke. It’s wonderful.”

Based in Raleigh, Restoration Systems has a long history of environmental mitigation banking, which means the firm does work to improve ecology, receives government credits for that work, then sells those credits to public and private agencies doing construction projects. Potentially worth millions, these credits help builders speed projects that might otherwise get mired in red tape or be permanently stalled.

In past years, Restoration Systems has taken out dams on both the Deep and Little rivers, and it has roughly 40 mitigation sites in North Carolina. “We found the bass fishing actually got better down at Carbonton Dam,” said George Howard, the firm’s president, speaking of the Deep River project. “That went from a stagnant impoundment to a free-flowing, burbling river.”

In February, Restoration Systems sent a prospectus to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, proposing to take out the Neuse dam roughly 15 miles downstream of the Falls Lake dam, freeing up an estimated 29,000 linear feet of water. The firm cited backing from state and federal agencies and called the dam a barrier to shad, striped bass and other migratory fish.

“There’s been an unnatural barrier there for 100 years,” Howard said. “It’s done horrible things to the ecology of the river.”

Alissa Bierma, who, as Neuse riverkeeper, advocates for and monitors the river, backed the dam’s destruction. Shad are plentiful just below the dam, she said, and above it, the wetlands aren’t well-functioning. “We don’t like dams,” she said. “It’s an unnatural change we have a chance to correct.”

But to those along the river, there’s nothing natural about the Neuse’s flow.

It’s already backed up by an enormous dam holding Raleigh’s water supply. Milburnie Dam predates the Civil War, when it was wooden and helped run a paper mill. In the 100-plus years that water has backed up behind it, wildlife has flourished there. If anything, residents say, the altered Neuse is the more natural version.

Neighbors object

Retired lawyer Jerry Alvis took a tour from his home a few miles above the dam in the middle of the day recently. Beavers, water snakes, hawks, herons and turtles all could be spotted along the riverbanks.

“This is the prettiest part,” he said. “This could be a green version of San Antonio’s River Walk.”

Both he and Smallwood say they regularly pull huge catfish and bream out of their portion of the Neuse, not to mention striped bass that come through the Falls Lake dam.

The water isn’t stagnant, they say; it’s flowing over the dam at a rapid clip. As he navigates the Neuse bends, Alvis’ boat hits bottom twice. Imagine the ride, he said, with the Neuse made shallower. How many fishermen, he asked, will come there?

The true motivation is money, not ecology, said Smallwood. He and his neighbors only received notice a few weeks ago, and they were told to comment by today.

“The 800-pound gorilla,” Smallwood said, “is the city of Raleigh.”

The city’s stake

So far, Raleigh hasn’t made a formal comment on plans for the river that runs along its eastern edge. And it may not, said greenway planner Vic Lebsock. Plans call for building a trail along 28 miles of the Neuse’s shore – a $30 million project. So far, the first phase downriver from Falls Lake has been authorized for $1.4 million. The city owns considerable land along the Neuse, including around Milburnie Dam, but the money isn’t there yet to develop parks. The effect on those Neuse plans, or the city’s canoe launches, is uncertain, Lebsock said.

“How much is the water going to go down?” he asked. “We don’t know at this point.”

The city is hoping the Corps of Engineers will extend the public comment period for at least 30 days. One potential, City Manager Russell Allen said, would be purchasing the credits from Restoration Systems to aid construction of a Little River reservoir in eastern Wake County – part of Raleigh’s long-term water supply plans.

Corps officials caution that everything from Restoration Systems’ calculations to details of its plan must be scrutinized and that the Little and Neuse river projects are completely unrelated.

Meanwhile, Smallwood said he hopes public comment will turn the Neuse dam’s tide and that opposition won’t come to a lawsuit.

Besides, he said: Nobody much likes eating shad. Too bony.

josh.shaffer@newsobserver.com or 919-829-4818

SHAD CLOSE TO HOME

Pete Benjamin, a field supervisor for the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Raleigh, fishes for American shad near the Milburnie Dam.

Raleigh News & Observer, Thursday, April 15, 2010

SHAD CLOSE TO HOME

Read more: http://www.newsobserver.com/2010/04/15/437433/shad-close-to-home.html#ixzz0lqB8qyqS

BY JAVIER SERNA – STAFF WRITER

RALEIGH — A 2-pound American shad hen danced along the Neuse River’s surface and spun line off a medium-action spinning reel like a spool of kite string at the other end of a steady Atlantic breeze.

The scene is most common toward the coast, but there’s no need to truck down to the coast to satisfy the saltwater fishing urge.

For a couple of weeks, American shad have been concentrating at the Milburnie Dam in Raleigh, nearly 230 river miles upriver from the Pamlico Sound.

“They’ve come a long way,” said John Ellis, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who spends many spare spring hours pursuing American shad for the fun of it. “We’re pretty high up in the watershed.”

The American shad is one of several species that have been able to reach their former spawning grounds ever since a downstream dam was removed 12 years ago.

An electroshocking survey conducted near the Milburnie Dam last week by N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission biologists turned up several dozen American shad and even a couple of striped bass, typical of spring sampling for the past 10 years.

“It suggests that these fish are taking advantage of the spawning habitat in the upper part of the river,” said Bob Barwick, a state fish biologist.

Earlier in the spring, hickory shad, the smaller cousin of the American shad, also ran up the Neuse, the longest river that is completely within the state’s boundaries.

Ellis and several of his colleagues aren’t the only ones who get a kick out of fishing for shad during a run that typically lasts into May. Others use fly rods to cast brightly colored “junk” flies with success.

There’s no telling how many fish are kept, but state law allows a combination of 10 American and hickory shad to be kept per day, unless the angler is fishing the Roanoke River, where only one of those may be an American shad.

“They’re tasty,” said Ellis, who said he would like to see the limit for American shad lowered on the Neuse to help protect the species.

The state has considered doing so but has decided it against for now, Barwick said.

In North Carolina, American shad tend to spawn more than once in their lives. On the Neuse River, American shad could go only as far as the Quaker Neck Dam near Goldsboro until 1998, when the dam was removed, opening up 78 more miles of river.

The low-head dam had been built in 1952, and its removal reopened old spawning grounds primarily for American shad and striped bass.

The American shad population in the Neuse is viable enough that, until this year, state biologists removed shad from below the Milburnie Dam to be used in hatchery efforts to stock the Roanoke River, which has a struggling population of the species. Striped bass and hickory shad are more abundant on the Roanoke.

The collection stopped this year because, although there are still a few 4-pound females, considered good breeders, the numbers of bigger fish are dwindling in the Neuse.

“We’re worred about removing too many fish from the Neuse River,” Barwick said.

New water

A chance exists that more of the Neuse could be opened soon. An open comment period is being conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regarding a proposal to remove the Milburnie Dam, which would add 15 free-flowing miles to the Neuse, making the Falls Lake dam the new dead end for migratory fish. The comment period closes April 22.

<

The project is a priority of the N.C. Dam Removal Task Force, which consists of staff from several state and federal agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Work could start in early 2011.

But there is some opposition, according to Randy Turner, the project manager for Restoration Systems Inc., the private environmental restoration and mitigation company that is undertaking the project.

Turner said some landowners near the dam are upset that the water levels above the dam will drop, making navigation with mid-sized watercraft impractical.

“It will never be as high,” he said.

But Turner said that aside from providing fish passage, the project will improve water quality, restore the natural habitat and aquatic community, and help up to eight state- or federally listed species of mussels and fish that were historically present in pre-dam conditions.

During rainy years such as this one, American shad tend to migrate higher up in the watershed in search of shallow rocky areas, which they prefer as spawning habitat. More of those areas await farther upstream.

Besides dam removal, American shad would be helped by more water.

The Army Corps, which regulates the water releases from Falls, has given more consideration to the needs of the spawning fish, Ellis and Barwick said. Informal discussions have been held about scheduled water releases.

“We’d like to see it a bit more formalized,” Ellis said. “It would be good for the fish if they would give us more water on a more regular basis in the spring, when the flows are high.”

Waders helpful

For now, the Milburnie Dam is the dead end.

For anglers, carefully wading out on the rocky ledge just in front – ideally with felt-sole boots and chest waders – is an option. And calmer pools inside 100 yards downstream from the mason structure also hold American shad.

Regardless, most prefer to stalk shad in waders rather than be confined to stream’s edge.

“It certainly opens up your options,” Ellis said. “That’s the advantage. You can get away from people.”

From the bank, Ellis caught a buck American shad within a few casts.

“We’ll invite him to dinner,” he said.

But the shad declined the invitation and slipped from his grip, escaping to the muddy waters of the Neuse.

Several hundred yards downstream of the dam, hand-tied shad rigs consisting of a small spoon and dart were cast out into the current with medium-action spinning gear.

First, a shad in the 1-pound class was hooked. It had about the same amount of fight in it as an equally sized hickory shad. It bled from a deep hookset and was kept for the table.

The next fish was twice the size, full of eggs, and it tested the drag system of medium-action spinning tackle. An acrobatic fish, it was coaxed to the water’s surface more than once, each time making a desperate run back into the murky, muddy water. Eventually, the hook was carefully removed and the fish was slipped back into the river.

With any luck, the descendents of that fish will be back in four or five years.

Read more: http://www.newsobserver.com/2010/04/15/437433/shad-close-to-home.html#ixzz0lqAhAlxE